07 December 2025

The July 2024 uprising was destined to usher in significant changes not only in Bangladesh's political system but also in its social and cultural environment. The rise of Jamaat-e-Islami and other Islamist groups has already been covered in detail by our previous reports, including their imprint in the socio-cultural spaces. This analysis by Tapas Das and Debayan Das points to far greater transformations becoming evident in the Bangladeshi polity. Citing the increasing instances of moral and cultural ‘policing’ by various fundamentalist groups, and pushing for a ‘puritan’ transformation, the authors argue that at stake is not just the future of religious minorities in the country, but also a forced transformation of the cultural identity of its citizens.

Home and text page images are (Deep) AI-generated and for representational purposes only

Banner image: Idols being ferried during the Durga puja for Pratima Visarjan in Bangladesh, photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

The July 2024 uprising would mark a significant turning point in Bangladesh’s socio-political history. While two significant uprisings occurred in 1969 and 1991 against the military or military-backed government on this soil, this time, it was against the democratic government.

Every uprising had brought changes to Bangladesh’s political history. If the 1969 uprising laid the foundations for the liberation movement, the 1989 uprising brought a second wave of democracy to Bangladesh.

However, neither of these two could instil secular, socialist, and democratic values, which were the motto and aspirations of political leaders and a large portion of the Bangladeshi people before the liberation. Consequently, the new constitution of Bangladesh outlined these values in 1972.

The 2024 uprising also gave the impression that it would be a momentous turn towards an inclusive Bangladesh, as aspired to since 1971. However, the hope is fading over a year later.

Since August 2024, new patterns of politics have become apparent in Bangladesh, both in nature and intensity, unlike before. These include mob violence, attacks on spiritual shrines and the garment industries, social constraints placed on musical concerts, and so on.

However, this report zeroes in on a previously unrecognised yet pivotal shift: the rise of body-focused moral policing by state and non-state actors. This trend, marked by religious extremism, is altering the contours of Bangladesh's politics and social life.

Recent incidents and trends

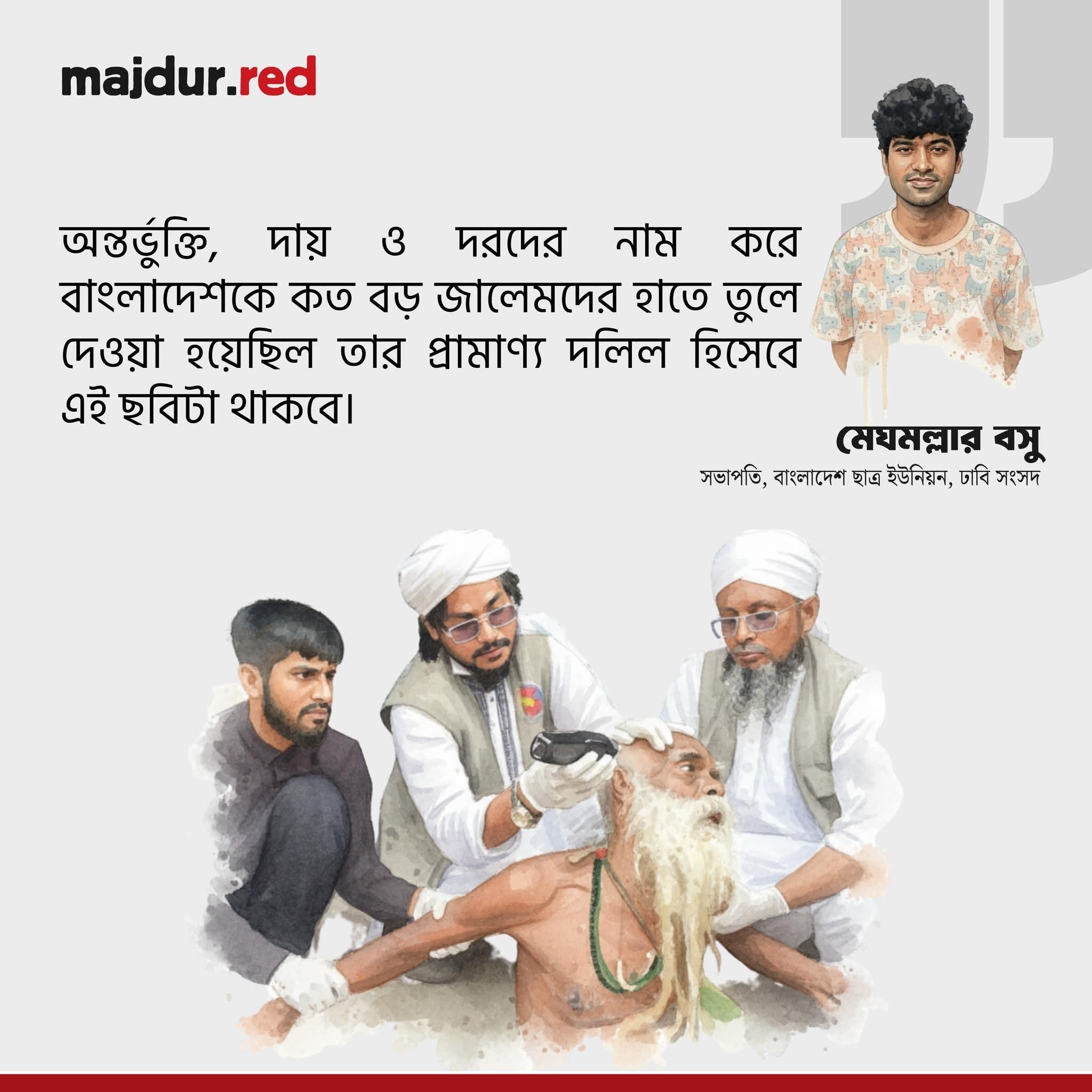

A video clip is going viral of an elderly Fakir (or Faqir, which refers to a Sufi mystic who undertakes spiritual practices and lives a life of asceticism) walking down a street when three men in grey vests begin to chase him. Before he could realise what was happening, they pinned him down and forcibly shaved his hair. As his locks fell to the ground, the Fakir cried out, “Allah, tui dehis!” (Make note of it, Allah).

Image: Some men forcibly shaving the hair (left) of a 70-year-old fakir, Halim Uddin Akand (right) in Kodalia Kashiganj village of Mymensingh's Tarakanda upazila. Halim Uddin Akand said, “I was sitting at home, they dragged me out and did this to me.”

The incident immediately drew severe condemnation. A lawyer at the Bangladesh Supreme Court, Jyotirmoy Barua, termed the act a “serious violation of fundamental rights.” The human rights body, Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), condemned the act as “inhumane and unlawful,” citing Articles 31, 32, and 35 of the Bangladesh constitution, which protect dignity, personal liberty, and prohibit degrading treatment.

Furthermore, the Baul singer Shofi Mondol opined: “They’re catching pedestrians, shaming them, cutting off their hair and beards that took years to grow. I, too, have long hair and a beard, so I understand the pain these ascetics are going through. I don't know what benefit they get from hurting people.”

There were multiple incidents of forcible hair-cutting and social humiliation in recent months: in June, people shaved a woman’s head over dowry demands in Lakshmipur; in July, a woman’s head was reportedly tonsured and stripped naked in Gaibandha for an alleged extramarital affair. Earlier, in March, a 19-year-old young man allegedly took his own life after a union parishad member forcibly cut his hair to shame and discipline him publicly.

In October, a mob desecrated Nura Pagla's tomb in Rajbari by digging out a freshly-buried body and setting it on fire on a highway. According to law enforcement sources, hundreds gathered under the banner of the “Tawhidi Janata”, accusing Nurul Pagla’s burial site of grossly violating Islamic principles. The interim government condemned these acts, terming them as inhuman and heinous crimes.

Incidentally, Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami has also expressed concern over the incident.

In Madaripur, people cut down a century-old banyan tree, accusing it of promoting shirk (in Islam, idolatry, polytheism, and the association of God with other deities). The cutting down was following an allegation that some women had committed shirk by placing sweets and other items at its base and tying red clothes to the tree. While the locals consider the tree a god and worship it, it is supposed to be forbidden in Islam for ascribing a partner or rival to Allah.

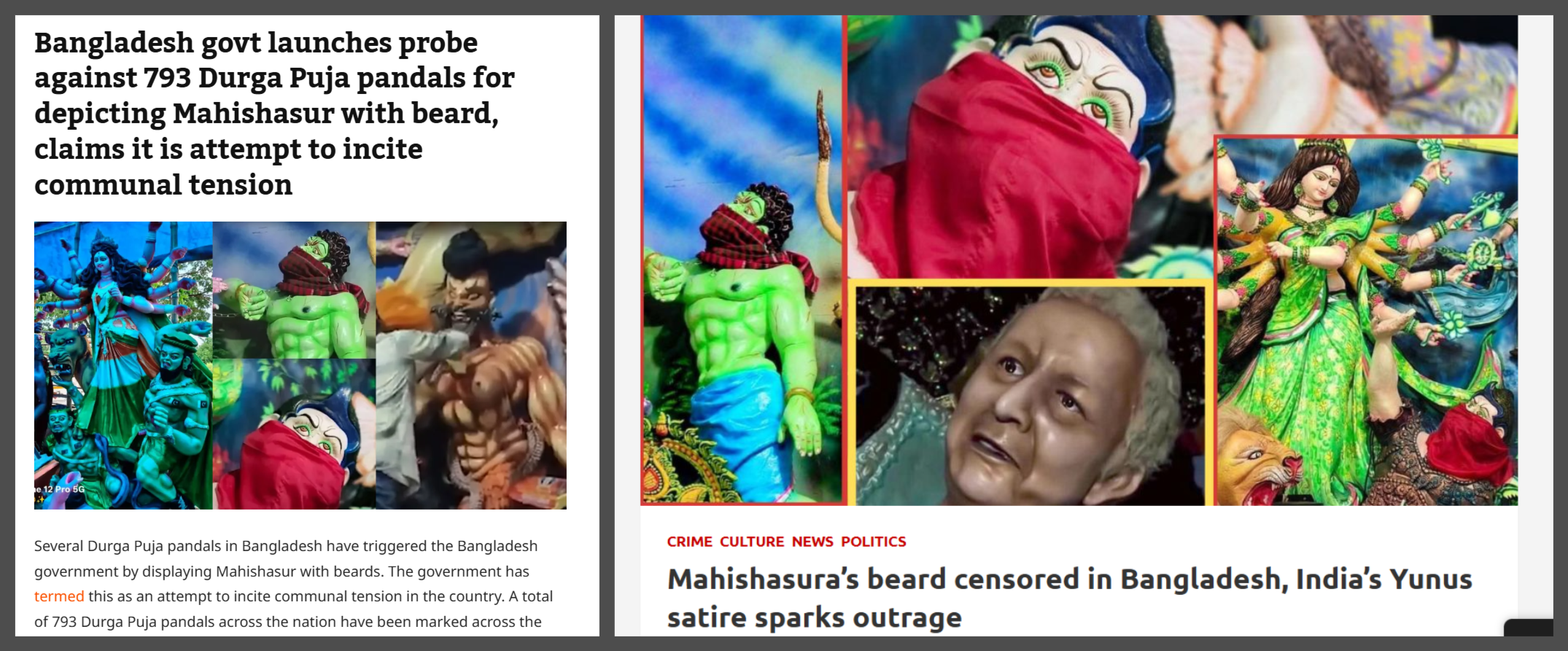

Idolatry and other symbols that could have a religious connotation also do not escape this kind of policing. A controversy recently raged in the Bangladeshi media over the beard of the Asur.

The concept of Asura has two distinct meanings: the mythological demon Mahishasura, whom the Goddess Durga slays, and the Asura tribal people of eastern India, who mourn Mahishasura's death. Shuklal, the general secretary of the Millain Phulbagan Harijan Mandir Committee, said that on the night of October, local policemen had ordered him to remove the Asur's beard.

Image: (The Home Affairs Advisor, Lieutenant General (Retd) Jahangir Alam Chowdhury, informing that the police received complaints of beards being placed on the faces of demons at over 793 puja mandaps across the country.)

Similarly, a 38-second Facebook video that went viral shows a ‘mob’ harassing a young woman by confronting her over 'Orna' (a long scarf, shawl, or veil worn by women in South Asia), and questioning her religious identity.

Saleh Uddin Sifat, a leader of the National Citizen Party (NCP), formed by student leaders of the July uprising, demanded that the culprits “be brought to justice immediately for harassment,” failing which “many other extremists will be interested in this work.”

The politics of moral policing

These incidents, grounded in religiously motivated moral policing, are not isolated. Instead, they expose a profound political and social transformation: a deepening intervention into bodies, behaviour, and symbols as expressions of power. This trend fundamentally diverges from Bangladesh’s previous pluralist ideals.

Instead, they suggest a more profound transformation, one that reflects the current character of Bangladeshi politics and the power dynamics of all the actors who increasingly influence the nation’s social fabric. The recurrence of such incidents under the current regime is not in line with the historical trajectory of the Bangladeshi community, which has prided itself on upholding the ideals of pluralism and inclusivity. These values were deeply rooted in its linguistic struggles, cultural syncretism, and communitarian practices.

What then has changed, and why are such incidents surfacing now?

‘Body’ as the subject of religious morality

These questions cannot be reduced to mere political expediency or electoral tactics. Instead, they demand a nuanced engagement with profound transformations in Bangladesh’s body politics. A careful observation of current politico-social developments would reveal one of the most striking developments in contemporary times – the visible politics of the ‘body,’ which becomes the central site of both power and resistance.

In the case of Bangladesh, this politics of the body does not confine itself to human bodies alone; rather, it extends to non-human and symbolic structures and entities, including idols, icons, and sacred spaces that have become objects of contestation. This extension of power to non-human and symbolic entities is most evident in the recent controversy over the beard of the mythical Asur (demon), Mahishasura.

The body has now become the battleground on which competing visions of the Bangladeshi nation inscribe themselves. Contrasting the historical narrative of inclusivity that shaped Bangladesh’s early imagination, the emerging narrative is based on religious exclusivity and seeks to define the nation in puritanical and exclusionary terms.

These competing regimes of power engage in a struggle that manifests itself essentially in corporeal terms, wherein what constitutes ‘the ideal body’ is defined on puritanical lines, which the collective imagination of the nation must accept, represent, and preserve.

Thus, Islamists shape rules and imagery about ‘the ideal body’ to embody the nation’s ideals. They discipline, regulate, and, at times, even violently correct the alleged ‘deviants,’ in order to force adherence to the dominant narrative. We could understand the violent attack on an elderly fakir and other similar incidents described earlier, through this framework, wherein this politics of the ideal body was exercised on them.

The extension of this politics from human to non-human structures and entities is what is new and deeply unsettling in the contemporary Bangladeshi polity.

The desecration of Durga idols during the puja festival symbolizes this quest for control over culturally and spiritually meaningful symbols. Even though these idols are inanimate objects, they represent the collective identity, memory, and devotion of a community. Consequently, destroying them is an aggressive maneuver is also aimed at erasing historical memories and dictating the acceptable boundaries of public representation.

Thus, by disciplining both living and non-living bodies, the Islamists ensure that no potential site of resistance remains visible. This is, in fact, the visible ‘body politics,’ whereby a conniving regime enacts power not only through laws and institutions but also through the careful control of what people see, perform, and allow to exist.

This stems from a contest over the meaning of Bangladesh itself: whose Bangladesh are they imagining today? Is it the secular, plural Bangladesh we envisioned at its birth, or one currently being redefined through the prism of a singular religious identity?

Control over bodies, both living and non-living, becomes a means of answering that question in favour of the dominant power. The more the political regime struggles to assert its vision, the more visible this control becomes.

To have a nuanced understanding of this transformation, one must also recognise that earlier forms of power and identity in Bangladesh inscribed themselves on the ‘collective’ – be it through the ideals of secularisation, linguistic unity, and communitarian life that the nation has essentially imagined itself. Accordingly, the ‘body’ of a Bangladeshi was a site of inclusion, manifested in diversity of faith, while at the same time united in language and culture.

What we are witnessing now is a reversal of this trend wherein an attempt is made to redefine the national identity through the politics of exclusion and to construct a purified vision of belonging by marking certain bodies and symbols as alien or dangerous. This is the reason why the contemporary violence in Bangladesh is not merely about violence in corporeal terms, but it is also about a symbolic cultural erasure.

The struggle, thus, is not over religious identity alone, but also about the very imagination of nationhood. Moreover, to control bodies is to control narratives, which essentially leads to the rewriting of history itself. Thus, the challenge that Bangladesh faces today should be seen as more philosophical than political; it is about whether the country will be able to remember itself.

The ultimate question is thus not about what kind of Bangladesh they seek to construct, but whose Bangladesh they are imagining, and who is imagining it?

Across all these apparently scattered events, there is one hinge: the disciplining of bodies is becoming normalised. The concept of the ‘disciplining of bodies’ refers to the complex ways in which social, cultural, political, and institutional forces regulate, train, shape, and govern human bodies; the Bangladeshi case, however, extends this to non-human bodies as well.

This process is fundamental to the formation of individuals as complaint, productive, and recognisable members of a society. The body is not merely a biological entity but a social text—a canvas upon which power is inscribed and through which social norms are enforced.

Who are the agents?

The emergence of a new moral regime in Bangladesh, which is grounded in religious exclusivity, reveals a complex reconfiguration of power. Unlike earlier moments of direct state control, the current moral order is produced not solely through coercive apparatuses but through dispersed, often invisible agents that shape social sensibilities from within.

These agents include organised fundamentalist groups, such as the ‘Tawhidi Janata,’ as well as unorganised vigilante actors, including mobs and segments of the ‘local orthodox people,’ all of whom collaborate, wittingly or unwittingly, to define and enforce a puritanical social norm.

This form of power does not require constant enforcement, but its success manifests in its invisibility. This leads citizens to see moral conformity not as an external demand, but as a self-evident good.

Thus, the new moral regime in Bangladesh operates simultaneously through normalisation and punishment, through invisible persuasion and visible correction. The ethical subject of contemporary Bangladesh is not simply ruled but produced through an amalgamation of networks of invisible agents that define virtue, belonging, and faith.

Their invisibility is the very condition of their decisiveness.

Image: A young leftist student leader, Meghmallar Basu, had this to say about the forcible tonsuring episode: “This picture will stand as a documentary in the future, showing how Bangladesh was handed over to so many great oppressors in the name of inclusion, responsibility, and compromise.”

The future of inclusivity

The increasing instances of moral policing in Bangladesh are more than a series of isolated criminal acts; it is evident that the public manifestation of a power shift is underway. The ability of non-state actors, such as the Tawhidi Janata, to enforce their version of morality with relative impunity signals a severe erosion of state sovereignty and the secular contract upon which the nation was founded.

When a hair, a dead body, an ancient tree, or a mythological idol becomes a battlefield for enforcing moral conformity, the inclusive Bangladesh aspired to in 1971 becomes a distant memory.

The crucial question is whether the state can reassert its monopoly on law enforcement and protect the fundamental rights of all citizens—living and dead—before this vigilantism fully entrenches itself as the new mechanism of governance.

The struggle is not simply over religious identity, but over the very imagination of nationhood and how Bangladesh will choose to remember itself.

(The views expressed in this report are the authors' own.)

Follow us on WhatsApp

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X @vudmedia