28 February 2026

The declaration by the head of Bangladesh’s interim government, Muhammad Yunus, that elections will be held in the country by February next year had set the cat among the pigeons in the fractured Bangladeshi polity. While most parties have been critical of this declaration - made in a foreign land and after a controversial meeting with the BNP chief - the question remains moot whether even this timeline can be realistically met, going by the conditions set by Yunus for the successful conduct of polls. As the political churning continues in Bangladesh with parties intensifying their electoral preparations, all eyes are on Yunus, whose political game plan remains ambiguous, as well as the role likely to be played by the Army and the party formed by the students who led the July uprising.

Bangladesh’s interim government chief adviser Professor Muhammad Yunus and Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) acting chairman Tarique Rahman agreed that the next general elections could be ideally held in mid-February 2026 if all preparations can be completed by that time. The exchange of views happened during their meeting on 13 June 2025 at The Dorchester hotel in London, where Yunus was staying as part of his four-day official visit to the United Kingdom.

Yunus, though, also described the ‘preparations’ as including “sufficient progress in reforms and trials,” that will need to be made by that time in order for elections to be held in February 2026.

Interestingly, a week earlier, when the Chief Adviser had announced that the national elections would be held on any day in the first half of April 2026, the BNP had rejected this timeline and insisted on the polls being conducted by December this year, a demand echoed by the Bangladesh Army as well.

Jamaat-e-Islami has vehemently stated that the meeting is “ethically unjustified” and represents a “deviation from the country's political culture.” The party expressed concern that Yunus, as the head of an interim government, should maintain strict neutrality and avoid appearing to show “special affection for a particular party.”

They further criticized the decision to hold a joint press conference and issue a joint statement abroad with a single political entity on matters of national importance.

They further criticized the decision to hold a joint press conference and issue a joint statement abroad with a single political entity on matters of national importance.

The National Citizens Party (NCP) Chief Coordinator Nasiruddin Patwary, for his part, has said that the people of Bangladesh should not accept decisions taken abroad on national issues. “The election date will not determine the future of Bangladesh. Without national consensus on justice and reform issues, a specific roadmap, and visible progress, elections cannot be held in the country in a hurry under pressure from any party,” Patwary remarked.

However, some of the Islamist parties welcomed the London meeting and declaration of the election date. The BNP Standing Committee member Salahuddin Ahmed claimed that the election timeline announced by Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus aligns with a proposal earlier made by Jamaat-e-Islami's Ameer, Shafiqur Rahman.

The London meeting, and the BNP’s changed position, raise many questions:

1) Why has the BNP shifted from its previous position?

2) Why was this meeting important for the transitional government?

3) If there will be an election in February, what will be the political equation?

4) What will be the role of the army?

For the BNP, the return of Tareque Rahman is important for their political future. BNP is still unable to fill the political vacuum of leadership after Sheikh Hasina’s exit.

On 6th May, Khaleda Zia, former Prime Minister of Bangladesh, and chair of the BNP, returned to Bangladesh from London after checking up on her health issues. No serious health issues were found. However, she has remained aloof from any political statements on the country’s ongoing developments. It is widely believed that Zia now wants his son to return to Bangladesh and fill the leadership vacuum of the country along with boosting the political activities of BNP.

However, several legal cases have been filed against Tarique Rahman. He was previously sentenced to life imprisonment for organizing the 2004 Dhaka grenade attack but was later acquitted of the charge in 2024. His associates claim the charges were politically motivated.

Nonetheless, it will be risky for Rahman to return to the country until these cases are formally withdrawn. The meeting with Yunus, it is assumed, could pave the way to resolve this conundrum and enable his safe return to Bangladesh, and, consequently, to the nation’s politics.

But why would the transitional government do so a favour for the BNP? It is well acknowledged that Yunus is working behind the scenes for the formation of the Jatiya Nagorik Party (NCP) – the political group formed by the students who led the July 2024 uprising that led to Sheikh Hasina’s ouster.

On the other hand, observers see a political motive in Yunus meeting Rahman in London.

A murky political milieu

The political culture of Bangladesh has long been dominated by the Bangladesh Awami League and Bangladesh Nationalist Party. Yunus seems aware of the fact that the political culture of Bangladesh cannot be easily transformed, notwithstanding the popular uprising.

Hence, prolonging the existence of the Jatiya Sarkar (National Government) and promoting it as a suitable alternative to the corruption-ridden political system will be Yunus’s game plan, which will also ensure his continuance in power.

As the largest biggest political party, currently, the BNP’s support will be critical in changing the political status quo, besides resisting the challenge from the Awami League and other parties, as well as the powerful Army. Mooting this strategy was the transitional government’s decision of 10th May to ban the Awami League (AL), the country’s oldest political party, led by Sheikh Hasina, from pursuing all activities in the country.

Historically, Bangladesh’s electoral landscape has been dominated by the rivalry between two prominent female leaders, often referred to as the “Battle of the two Begums.”

Historically, Bangladesh’s electoral landscape has been dominated by the rivalry between two prominent female leaders, often referred to as the “Battle of the two Begums.”

Despite the absence of Sheikh Hasina in Bangladesh since 5th August, her arch-rival, the BNP, has failed to control the political spectrum. Regarding the ban on the Awami League, G.M. Quader, Chairman of the Jatiya Party, stated that his party does not favour banning any political party. Gayeshwar Chandra Roy, a BNP Standing Committee member, commented that banning political parties does not solve all problems.

This perspective likely reflects their concern that the same legal measures could be applied to them soon. Perhaps that is why BNP high commands and leaders want an election at the earliest.

Khaleda Zia’s return to Bangladesh, on the other hand, would potentially bring about a shift in the country’s political landscape, particularly given the perceived leadership vacuum. While Begum Zia has remained politically silent for several months, her inactivity might indeed suggest an impending leadership transition within the BNP.

Adding another layer of complexity is the National Citizen Party (NCP) leader, Hasnat Abdullah’s presence at a rally organised by Hefazat-e-Islam, a group protesting proposed changes to women’s rights.

Interestingly, the two major Bangladeshi parties have sought to align themselves with Islamic leaders/groups, or the Islamist bloc, to maintain their grip on power. The last decade witnessed the Awami League’s strategic support to the Hefazat-e-Islam, in order to counter the Jamaat-e-Islami.

A potential development could be the NCP forging a coalition of religion-based parties under its leadership, including the Jamaat as a political ally, while Hefazat and similar groups continue to maintain their social influence.

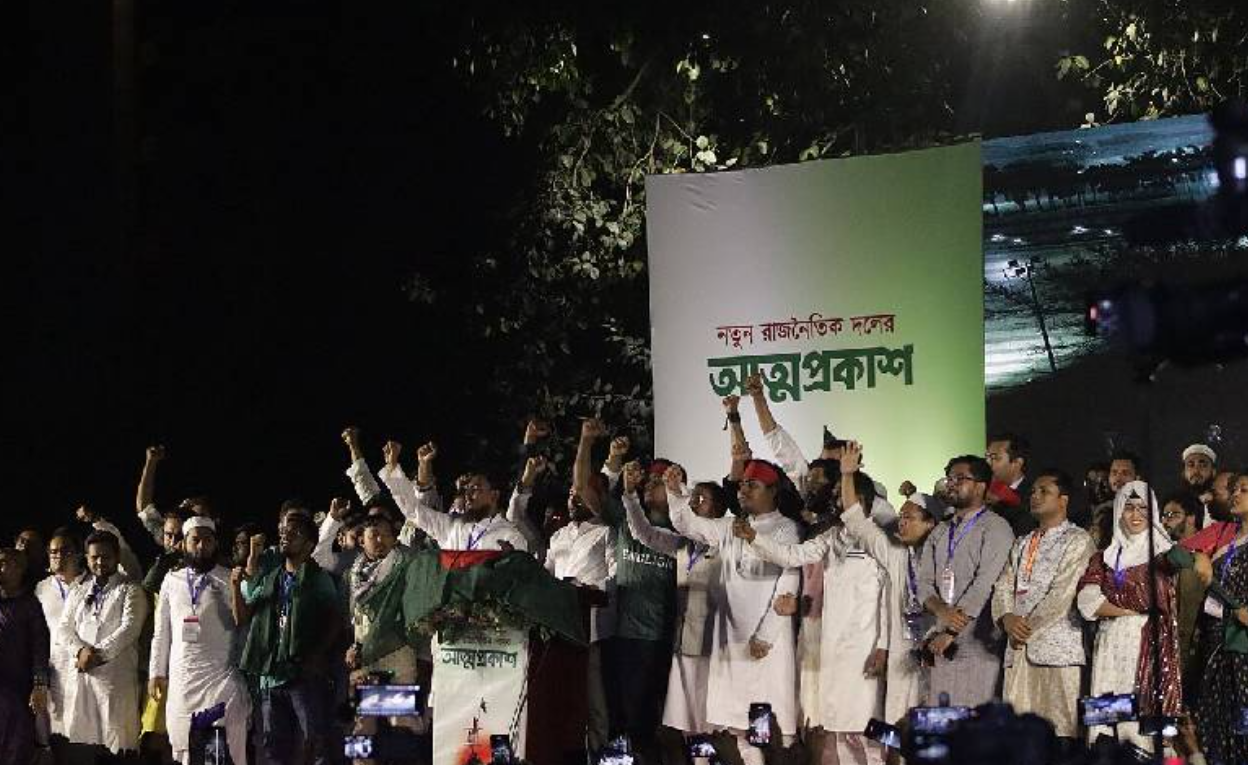

Furthermore, a new student-led political party, unaffiliated with the NCP, is expected to emerge by the end of May 2025. This follows a trend of several new political entities forming in recent months, all seeking registration with the country’s Election Commission. While these nascent parties may not currently hold significant political sway, they aim to gain some political foothold and economic advantages.

A deeper political churning at work?

The 10th May ban on the Awami League follows a similar action on 23rd October against the Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL), its student wing. The hiatus between these bans, however, is puzzling. It raises questions as to why the country’s student leaders, key to the movement that resulted in the August 2024 protests, did not exert pressure for this action earlier.

The answer may lie in the launch of the “Jatiya Jubo Shakti” on 16th May as the youth wing of the National Citizen Party (NCP). It is possible that NCP leaders believed that after the ban on the BCL, the younger cadre from the Awami League would automatically join the NCP to safeguard their political and personal interests. This, they hoped, will enable the NCP to expand its influence nationwide.

Perhaps this was the rationale behind setting the maximum age limit for members of the representative committee at 50 years, to attract the bulk of the Awami’s membership while leaving behind seasoned loyalists.

The BNP has been strategising on similar lines.

Ruhul Kabir Rizvi, BNP Senior Joint Secretary General, stated that individuals formerly associated with the Awami, who did not support or participate in its alleged misrule and had already distanced themselves from the party, were welcome to join the BNP.

This message is quite clear.

Interestingly, not all NCP leaders actively participated in the mass gathering at Shahbag demanding a ban on the Awami League. It was primarily demanded by the Hasnat Abdullah-led Jamaat-e-Islami and Hefazat-e-Islam supporters.

Previously, it was assumed that there were ideological differences among the Islamic groups and Islamist parties in Bangladesh. However, several instances of collaboration since July 2024 reflect that they are working in tandem. However, if elections are held sooner, they are not expected to maintain the same rapport at the hustings.

The former leaders of the Islamic Chhatra Shibir who were involved in the July uprising, and subsequently split from the NCP, are reportedly creating an alternate platform called United People’s Bangladesh or UP Bangladesh. These two developments suggest that the NCP’s strategy to attract Awami members is not succeeding. It is struggling to establish its political goals.

However, a report by BBC Bangla indicates that the conflict between NCP and Jamaat could be a political strategy of these two parties. The recent clash between activists of the BNP and Jamaat in Chattagram’s Jungle Salimpur area and the attack on the Jamaat rally allegedly by BNP men in Narayanganj suggests that the Jamaat is attempting to capture political space as a major political player.

However, a report by BBC Bangla indicates that the conflict between NCP and Jamaat could be a political strategy of these two parties. The recent clash between activists of the BNP and Jamaat in Chattagram’s Jungle Salimpur area and the attack on the Jamaat rally allegedly by BNP men in Narayanganj suggests that the Jamaat is attempting to capture political space as a major political player.

This could also imply that all Islamic and Islamist parties are not necessarily strategic allies of the BNP, NCP, or the Awami League.

Impending polls and a fractured polity

The question is moot whether the people of Bangladesh are ready to accept new changes.

BNP leaders, on expected lines, will be attempting to broaden their support base, both domestically and internationally, in order to maintain their political relevance. In the case of the NCP, a sharp fault line exists among its leaders. NCP leaders, having attempted to expand and consolidate their support base in their hometowns or districts, seem to have realised the difficulties of advancing from a political movement to a political organisation.

It is for this reason that the NCP echoed the demand of the Jamaat-e-Islami that not only the next national election but also local government elections should be held under a neutral government.

On the other hand, Jamaat seems to be aware of the limits of its influence in Bangladesh’s electoral politics. Accordingly, in the current situation, it could be left with two options: either form a bloc with other Islamic parties, which, though, could be a difficult endeavour considering the divisions among Islamic groups in the country, or, form an alliance with the NCP.

However, even after the banning of the Bangladesh Chatra League and the Awami League, their loyalists remain active in Bangladesh, creating a challenge for all political parties. In other words, the Awami League is still relevant in Bangladeshi politics though the other parties are well ahead in terms of the preparations for the election.

It is moot that Jamaat continues to have sharp differences with the BNP. It will, hence, be significant to observe how the Jamaat prepares for the upcoming election, especially since its vote base remains confined to three divisions: Rajshahi, Comilla, and Chittagong.

The NCP, for its part, has begun its campaign and is likely to gain some leverage after the proclamation of the “July Charter.” However, there are still no signs of a mass base for this party.

Going by the signs, it does not seem that the NCP is adequately prepared for the election. Hence, it is likely that the NCP leaders will use their leverage and role in the transitional government to further delay the election unless or until they are sure of victory.

On the other hand, Hindu votes and the women's vote bank are significant factors. If the BNP can successfully fill the political leadership vacuum, they will undoubtedly be the winning party. However, the internal dilemmas within the party might hinder its chances.

In the last few months, increased unemployment among women, atrocities against minorities, and negative comments regarding the women’s commission indicate that the NCP and the Islamic Bloc are distancing themselves from these vote bases, especially of the Hindu community. The BNP now faces the challenge of proving itself as a credible political force – not just as a party that wins elections because political situations favour them.

The Communist parties, meanwhile, could potentially revive themselves by capitalizing on the situation, particularly issues like unemployment and worker unrest. However, they remain more engrossed in ideological dialectics than impactful political action.

Army: The elephant in the room?

It's a widely held perception that the Army has played a significant, and, at times, controlling, role in Bangladesh’s transitional governments, particularly the “9/11 government” (referring to the caretaker government that took power on 11 January 2007, not related to the US events of 11 September 2001). This period, from 2007 to 2008, is frequently cited as an example of a military-backed regime operating under the guise of a civilian caretaker government.

At the same time, Army Chief General Waker-Uz-Zaman’s press briefing on 21st May indicates an impending shift in Bangladesh’s political landscape.

Key highlights of this press briefing were as follows:

1. The Chief of Army Staff (CAS) reportedly stated that there would be no Humanitarian Corridor, nor any port allotted to any foreigners, till an elected government came to power in the country.

2. The CAS expressed serious concern that the interim government is making key decisions while keeping the armed forces in the dark. He firmly stated that elections must be held by December and that only an elected government should determine the nation’s course – not an unelected administration.

3. Zaman pointed out the importance of the 1972 Constitution of Bangladesh and stated that any large-scale changes are not desirable.

4. The officer corps stands united in support of the CAS and is ready to act upon command.

5. The Army will no longer tolerate mob violence or lawlessness, signalling a shift toward stricter enforcement of order.

The Army has always maintained a pivotal role in Bangladesh’s politics. Two army generals have served as heads of state in Bangladesh, besides the Army attempting to seize political power on multiple occasions.

However, this time, the Army’s stance is restrained and nuanced, with General Waker-Uz-Zaman declaring that he has no political ambitions. The Army chief has also been emphatic about his desire for the Army to return to the barracks and for political stability to be achieved through democratic processes.

The Bangladeshi army is unlikely to directly intervene in the political process, partly due to its delicate relationship with India. Recent Indian suspensions of imports from Bangladesh of its readymade garments, fruits, and processed food through land ports, now limited to Kolkata and Nhava Sheva seaports, complicate the narrative of anti-India factions. These suspensions highlight a more nuanced reality in the bilateral relationship.

Concurrently, the “push-ins” of individuals by the Indian Border Security Force (BSF) into Bangladesh continue, with 28 reported detentions by Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) on May 17th. Despite these tensions, open-door diplomacy, including a BGB-BSF flag meeting in Chuadanga on the same day, offers a hopeful sign for both nations.

Furthermore, in a significant development, Bangladesh will, for the first time in its history, engage a foreign company to operate a port. Interestingly, this Saudi-based operator reportedly has a strong relationship with the U.S. This raises the question of whether the U.S. might be using this company as an indirect way to establish a presence in the Bay of Bengal.

Bangladesh is also at the centre of a diplomatic discussion regarding a UN proposal for an aid corridor to assist those affected by the violence between Myanmar’s military junta and the Arakan Army. While seemingly aimed at alleviating the suffering of displaced Rohingyas, concerns exist about the proposal’s potential to exacerbate the crisis and its implications for the Bangladeshi Army if they were to become involved.

Bangladesh is also at the centre of a diplomatic discussion regarding a UN proposal for an aid corridor to assist those affected by the violence between Myanmar’s military junta and the Arakan Army. While seemingly aimed at alleviating the suffering of displaced Rohingyas, concerns exist about the proposal’s potential to exacerbate the crisis and its implications for the Bangladeshi Army if they were to become involved.

The meeting between Yunus and Tareque was significant from another perspective as well. Yunus had declined the Army’s election proposal, and Tareque's past experiences with the Army had not been encouraging either.

For Muhammad Yunus, establishing a national government with him as President could offer a critical pathway to not only definitively replace the influence of the former Awami League government, but also significantly curtail the military's direct role in politics.

This move would leverage his international stature and the current political vacuum.