21 February 2026

Following the protests against the ruling regimes in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, it was the turn of Nepal to implode against institutional and political corruption in September 2025. It was the GenZ that spearheaded this movement to oust the Nepalese government, which was marked by widespread attacks on the dominant political class, across the nation. Like in the case of the Mohammed Yunus-led interim government in Bangladesh, a retired chief justice, Sushila Karki, was assigned to helm the interim arrangement and facilitate elections to the Nepalese Parliament. In the scheduled elections of March 5th, new political forces, including representations from the GenZ are slated to take on the ‘Old Guard,’ which, surprisingly, are trying their luck despite the nationwide outrage already expressed against their brand of politics. In this two-part series, Dewkala Tamang and Tapas Das explore the impending political transformation in Nepal.

Home page image: A ballot box representing the election in Nepal

Text page image: Interim Prime Minister Sushila Karki with the GenZ group leaders who led the protest of September 2025

Banner image: Candles around the Nepalese flag during a vigil to mourn the death of protestors

Following the Gen-Z protests in September last year in Nepal and the resignation of K.P. Sharma Oli, an interim government was established under former Chief Justice Sushila Karki on September 12th, similar to the arrangement in Bangladesh.

Following the footsteps of the latter, Nepal has also entered a decisive phase of its democratic transition. Tasked with steering the nation through the aftermath of the Gen-Z-led uprising, the Sushila Karki administration has formalised March 5, 2026, as the date for a single-phase nationwide election to the House of Representatives.

This commitment to a transparent transition is being matched by rigorous logistical readiness.

Symbols of the political parties - Ujyalo Nepal Party, People's Socialist Party, Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist-Leninist, and Rastriya Swathantra Party

The Election Commission confirmed that the printing of over 41 million ballot papers – including 20.3 million for the First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) system and 20.83 million for the Proportional Representation (PR) system – was completed by February 16, 2026, at the Janak Education Materials Centre in Bhaktapur.

These materials are currently being dispatched to all 77 districts, ensuring that even remote mountainous regions are prepared for the vote.

The 2026 election is also marked by an unprecedented focus on digital integrity and voter awareness in response to the social media-driven nature of the 2025 revolution. To counter the “deluge of partisan influencers” and misinformation, TikTok has launched a dedicated Election Centre in Nepal to provide authoritative information. Meanwhile, the Election Commission has issued strict directives against the use of AI-generated, misleading content.

Additionally, the Commission has requested that media organisations refrain from publishing opinion poll results to preserve a competitive electoral environment and prevent voter disillusionment.

As the campaign period concludes and security forces, including the Nepal Army and Police, are deployed to sensitive areas, attention is centred on whether these comprehensive logistical and digital measures will facilitate a peaceful election that addresses the reformist aspirations of the Nepali electorate.

With campaigning intensifying nationwide in anticipation of the House of Representatives elections, political parties and candidates are actively seeking voter support. The alliance formed by Rabi Lamichhane (Rastriya Swatantra Party), Balendra Shah (Balen), and Kulman Ghising (Patron of the Ujyalo Nepal Party) has introduced a significant new dynamic to the March elections (Ghising has since reportedly exited the alliance).

The emerging political leadership: Balendra Shah (left), Kulman Ghising (centre) and Rabi Lamichhane (right)

In response, established political leaders such as Sher Bahadur Deuba and K.P. Sharma Oli are working to consolidate a unified platform following their significant meeting on December 5, 2025. These traditional parties are contending with internal challenges as younger members advocate for systemic reform.

Although the leadership of the Nepali Congress (NC) and Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) (CPN-UML) initially anticipated that the Supreme Court might reinstate the dissolved parliament, this possibility is diminishing as the national elections draw nearer.

The forthcoming election is characterised by an unprecedented level of competition, with 68 political parties fielding 3,484 candidates for the House of Representatives. Among these, 2,297 candidates represent political parties, while 1,187 are independents.

The Election Commission has registered approximately 915,000 new voters since the finalisation of the 2022 list, increasing the total eligible electorate to over 18.9 million. This substantial influx of first-time voters is expected to significantly influence the nation’s political trajectory.

Notably, Nepal’s last majority government was formed following the 1999 elections; since then, coalition governments have prevailed.

The current electoral process remains complex due to the 2015 constitutional framework. The House of Representatives comprises 275 members, elected under a mixed-member proportional (MMP) system: 165 are elected under first-past-the-post (FPTP), and the remaining 110 are elected via party-list proportional representation (PR).

This dual structure makes it mathematically difficult for any single party to secure a clear majority, often necessitating the very coalition-building.

In addition to domestic reform, the March 5th elections serve as a catalyst for recalibrating regional dynamics. India and China, often described as Nepal’s “two elephants,” maintain distinct priorities. While New Delhi seeks a government supportive of its border and water-resource interests, Beijing emphasises stability to prevent Nepal from serving as a base for Tibetan nationalism.

Despite these divergent objectives, both countries fundamentally seek a stable Nepal. Effective navigation of these interests by emerging leaders could enable Nepal to transform its geographic position into a strategic asset rather than a geopolitical liability.

Amid these significant diplomatic developments, the 1,200-megawatt Budhigandaki hydropower project has regained national prominence. The government’s recent endorsement of a USD 3 billion investment model has positioned this reservoir-type project, the largest in Nepal, as a focal point of the election campaign.

The commitment by leading political parties to resolve longstanding impasses surrounding the project underscores Nepal’s broader efforts to convert its substantial water resources into the economic growth sought by the Gen Z electorate.

Attention has intensified as three leading candidates for the prime ministership are contesting from strategically significant constituencies. In Koshi Province, the contest in Jhapa-5 features former Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli facing a strong challenge from prominent youth leader Balen Shah.

In the Madhesh Province, Nepali Congress President Gagan Thapa is contesting the Sarlahi-4 seat against RSP-backed Amresh Kumar Singh. Additional key constituencies in Morang, Bara, and Rautahat, where veteran leaders such as Madhav Kumar Nepal are competing, are expected to play a decisive role in determining the composition of the next government.

A slogan of the protest (left), a call for protestors to gather (centre), and the actual protest (right)

Development of political parties and party-related laws

Nepal’s modern political history shifted from the absolute rule of the Shah dynasty and the 104-year Rana oligarchy to a burgeoning party system that began with the clandestine formation of the Praja Parishad in 1936.

While trailblazing organisations such as the Nepali National Congress and the Nepal Communist Party emerged in the late 1940s, they lacked legal standing until the 1951 revolution overthrew the Ranas. This transition was codified by the Interim Government of Nepal Statute (1951) and later the 1959 Constitution, which formally recognised the right to organise.

However, this democratic progress was abruptly halted in 1961 by the introduction of the party-less Panchayat system, which forced political activity underground for decades. The democracy movement culminated in the People’s Movement of 1990, which led to the 1991 Constitution, which reinstated the fundamental right to form political parties.

To support this new pluralistic landscape, a robust legal framework was established through the Election Commission Act 2073 (2017) and various electoral laws, creating a structured environment for the continuous evolution and regulation of Nepal's political parties in alignment with the country’s shifting governance systems.

Generational shift in Nepali politics

In the aftermath of the September 2025 unrest, a former chief justice, Sushila Karki, 73, was appointed as the interim prime minister to lead the Himalayan republic of 30 million people to elections.

Thousands of young activists first proposed her name via the online platform Discord. Karki is expected to step down after the vote for the 275-seat House of Representatives, the lower chamber of parliament, with 165 members elected directly and 110 through party lists.

Here are the key players in an election that many young Nepalis hope will usher in new leadership.

The old guard

Nepal’s political system operates as a closed elite circulation mechanism, often described as a “musical chairs” model, where power has rotated among a limited group of veteran leaders since 2006.

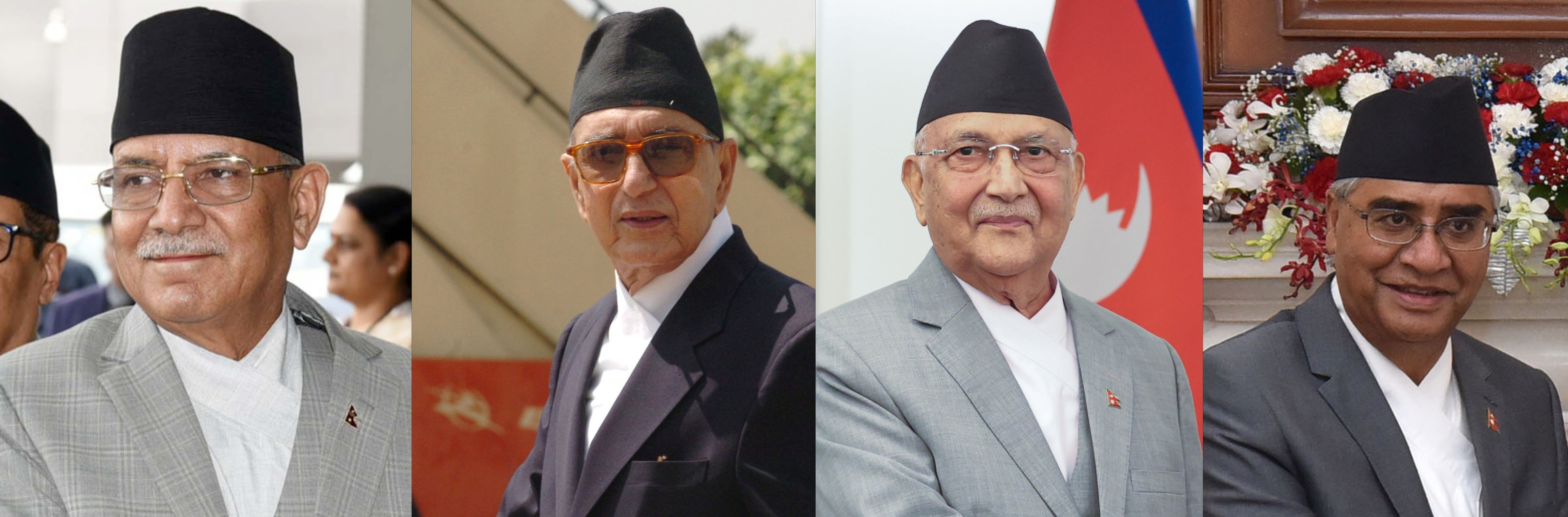

The 'Old Guard': Pushpa Kamal Dahal Prachanda, Girija Prasad Koirala, K.P. Sharma Oli, and Sher Bahadur Deuba - all past Prime Ministers

This gerontocratic dominance, exemplified by leaders such as K.P. Sharma Oli (73), Pushpa Kamal Dahal (71), and Sher Bahadur Deuba (79), has prioritised short-term coalition maintenance over substantive structural reform. Consequently, the state remains tactically unstable and strategically stagnant.

The recent election of 49-year-old Gagan Kumar Thapa as the president of the Nepali Congress marks a rare breach in this system, indicating an emerging shift toward generational reformism.

At the same time, the political system faces a legitimacy deficit, as public dissatisfaction has contributed to renewed monarchist sentiment, particularly through the Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP). This has produced a volatile institutional context in which the revolutionary establishment, including the former Maoists and the UML, must contend with both emerging youth-led movements and persistent traditionalist forces.

Nepal’s principal systemic challenge is to transition from a high-turnover patronage model to a more inclusive, institutionalised democracy capable of bridging the gap between an ageing leadership and a youthful, dynamic electorate.

Youth appeal

Nepal’s political system is undergoing a profound structural realignment as the “Old Guard” faces multidimensional challenges from populist and technocratic outsiders. The Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP), led by Rabi Lamichhane, emerged as a significant disruptive force by championing transparency and anti-corruption. However, the RSP now navigates a critical legitimacy crisis.

Lamichhane’s involvement in the Surya Darshan Cooperative fraud case, encompassing allegations of organised crime and money laundering, has placed the party’s future in the hands of the judiciary. With the Kaski and Rupandehi district courts halting the withdrawal of these cases pending a Supreme Court ruling, the RSP’s “Citizen Contract” manifesto serves as a strategic attempt to reclaim the narrative and provide a formalised alternative to the traditional parties that dominated the pre-2025 era.

This systemic shift is further personified by the alliance between Lamichhane and Balendra “Balen” Shah, whose candidacy for the Prime Minister represents a shift toward digital-age populism and performance-based legitimacy. Unlike traditional leaders, Shah bypasses legacy media to mobilise a vast youth electorate, framing the 2026 election as a direct confrontation between established patronage networks and a new, technocratic vision.

This trend is complemented by the emergence of Kulman Ghising, who leverages his reputation for administrative success at the Nepal Electricity Authority to advocate for a socialism-oriented economy. Ghising, who was the energy minister in the interim government, had resigned from the post to participate in the upcoming elections.

In January, Ghising’s Ujyalo Nepal Party also split from the alliance with RSP after a short-lived unity of 12 days. Ghising’s platform prioritises a ‘results-driven’ partnership between the state and the private sector, moving away from the ideological ambiguity that led to the collapse of previous alternative movements.

The dissolution of parliament in September 2025 and the subsequent call for snap elections have produced a high-stakes context in which the viability of emerging political forces depends on their capacity to institutionalise. Although the demand for systemic alternatives is clear, historical patterns indicate that momentum may dissipate without the establishment of enduring governance structures.

The outcome of the March 2026 general election will reveal whether leaders such as Shah and Ghising can evolve from anti-establishment figures into effective administrators, or if Nepal’s political system will revert to its traditional cycle of elite dominance.

The GenZ leaders: Sudan Gurung (left), K P Khanal (centre), Purushotam Yadav (right)

The Gen Z imprint

Meanwhile, a new cohort of first-time candidates has emerged from the loosely organised Gen Z movement that fueled Nepal’s September protests, as young Nepalis seek leaders promising economic reform amid stark challenges.

The World Bank estimates that 82 per cent of Nepal’s workforce remains in informal employment, with a GDP per capita of just USD 1,447 in 2024, underscoring the urgency for change. Among these rising figures is Sudan Gurung, a 36-year-old activist and pivotal leader in the Gen Z movement.

Following the protests, Gurung played a crucial role in facilitating dialogues with the Army chief, the President, and other stakeholders to form the interim government and appoint Sushila Karki as Prime Minister. When elections were announced, he worked to unite alternative forces around Gen Z mandates, ultimately joining the Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) in January alongside Balen Shah, Kathmandu's former mayor and the RSP’s prime ministerial candidate.

Gurung is now contesting the Gorkha-1 constituency under the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system. His activism began after the devastating 2015 earthquake, building on his earlier career as a DJ in Kathmandu's bustling Thamel tourist district.

Complementing Gurung’s campaign are other young trailblazers within the RSP and allied groups. Purushotam Yadav, 27, the Gen Z leader who secured official permission for the original September 8 protest from Kathmandu’s District Administration Office, is running on a proportional representation (PR) basis in the Tarai-Madhes region.

In an interview with Harbingers magazine, Yadav described the election as a “do-or-die” moment: “Traditional forces are against us. They do not value the sacrifice of Gen Z martyrs. RSP must get a majority in parliament to recognise and respect those sacrifices and to change Nepal's political landscape.”

KP Khanal, 26, Nepal’s youngest prominent social activist, has a background in environmental work and children’s rights—he launched a radio program at the age of 13—and operates a popular café in Kathmandu. Joining RSP from Balen Shah’s faction after the revolution, Khanal serves on the party's central committee and is contesting Kailali-2.

Similarly, Bablu Gupta, 28, made history as Nepal’s youngest-ever youth and sports minister in the interim cabinet after the protests but resigned in January to pursue a candidacy in Siraha-1 on the RSP ticket. As founder of the nonprofit 100’s Group, Gupta has long provided food, clothing, and emergency aid to low-income communities.

Other activists are carving paths through diverse challenges. Shiva Shankar Yadav, 30, a longstanding Gen Z figure, joined RSP's Central Committee after the September unrest and is standing in Siraha-2 in southeastern Nepal. Manish Khanal, a lawyer and member of the Gen-Z Front, represents the National Independent Party (NISP) in Nawalpur Constituency No. 2.

From Nepal's remote northern fringes, Tashi Lhazom, 26, advocates for climate justice and indigenous rights in Humla district. She gained prominence during the Gen Z protests when her name surfaced for a cabinet post, only to be withdrawn amid controversies over her citizenship and Tibetan heritage—fears tied to geopolitical tensions with neighbouring China.

Though endorsed on RSP’s PR list and initially slated for Humla, Lhazom’s candidacy was again removed without consent. In a candid exchange with Harbingers magazine, Lhazom reflected: “This election concerns my identity and the existence of my community, as well as Gen Z’s responsibilities.”

The GenZ leaders: Shiva Shankar Yadav (left), Manish Khanal (centre), Tashi Lhazom

On the cusp of a new epoch

These candidacies are emerging amid significant economic challenges and heightened international attention. Economic hardship has compelled millions of Nepalis to seek opportunities abroad, with 7.5 per cent of the population residing overseas according to the latest census; remittances from this diaspora constitute nearly one-third of Nepal’s GDP.

Although logistical constraints preclude diaspora participation in this election, their influence remains considerable. As a landlocked country situated between India and China, Nepal’s elections are subject to intense global scrutiny, with both neighbouring powers seeking to influence political developments in Kathmandu.

The elections on March 5th, thus, constitute a pivotal moment in Nepal’s contemporary political history, presenting the most substantial challenge to the traditional establishment since the restoration of democracy in 1990.

As the interim administration led by Sushila Karki transitions to a permanent government, Nepal is experiencing a structural transformation. The “Old Guard,” represented by leaders like Oli and Deuba, must now contend with a sophisticated, Gen Z-led movement.

This youth-driven uprising has extended its influence from public demonstrations to the electoral process, with figures like Shah and Lamichhane utilising digital platforms and anti-corruption agendas to mobilise nearly one million new voters.

The complexity of the 2015 constitutional framework, specifically the mixed-member proportional system, suggests that while these “new forces” have captured the national imagination, the path to a stable majority remains mathematically daunting. Historically, Nepal has been defined by a cycle of short-lived coalitions, and the current landscape, with over 3,400 candidates, indicates that the era of political fragmentation continues.

A soldier stands outside the burnt section of the Nepalese Parliament

Nevertheless, the rise of performance-oriented leaders such as Kulman Ghising and activists like Sudan Gurung reflects a transition from ideological discourse to concrete development objectives, exemplified by renewed attention to the long-delayed 1,200-megawatt Budhigandaki hydropower project. hydropower project.

Ultimately, the success of this political transition will depend on Nepal’s capacity to reconcile domestic aspirations with the complex geopolitical interests of India and China. As ballot printing nears completion and the RSP’s “Citizen Contract” emerges as a new standard for accountability, Nepal aims to move beyond its reputation as a “geopolitical burden” and position itself as a strategic intermediary.

Regardless of whether the election produces a clear mandate or ends up in another coalition, the integration of Gen Z activists into senior levels of governance will ensure that calls for transparency, economic reform, and social justice remain central to Nepal’s political discourse in the years ahead.

(Views expressed in this report are the authors' own.)

Follow us on WhatsApp

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X @vudmedia

Follow us on Substack