16 January 2026

Dr B.R. Ambedkar is India’s national icon whose role in nation-building is often confined to two distinct contributions – as drafter of the Indian Constitution and as a beacon of social justice. However, to reduce the movement of ‘Ambedkarism’ to a mere catalyst of social justice and anti-caste crusades would be an affront to his persona, intellect and ideology. To celebrate his legacy as one of India’s greatest nation builders, we need to commemorate Ambedkar as among India’s finest economists, a globally trained jurist, a rigorous lawmaker, and the most visionary labour-rights reformer this country has produced, says Rejimon Kuttappan.

Home page image: A photograph of Ambedkar during the drafting of the Constitution

Text page image: Ambedkar with Savita Ambedkar at ‘Dhamma Deeksha’ ceremony at Nagpur on 14 October 1956; photo source - Navayan

Banner image: A portrait and bust of Ambedkar unveiled at Gray’s Inn, where he was called to the bar in 1922 and completed his Bar at-Law degree; photo source – Dr B R Ambedkar’s Caravan

In today's India—especially among dominant political narratives in Kerala and sections of Ambedkarite politics—Dr B.R. Ambedkar is often reduced to a single identity: an anti-caste crusader. While this legacy is foundational, it is also incomplete.

Ambedkar was far more than a moral symbol of social justice. He was among India’s finest economists, a globally trained jurist, a rigorous lawmaker, and the most visionary labour-rights reformer this country has produced.

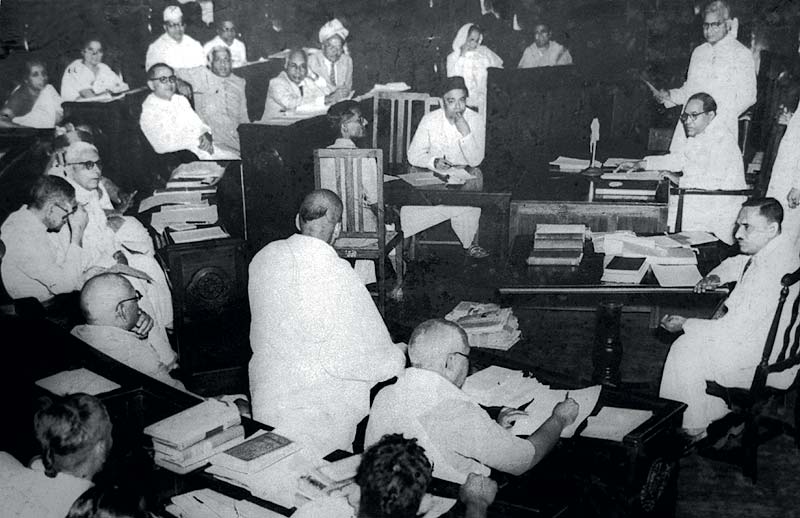

Image: Ambedkar chairing a session of what seems to be a Special Committee comprising members of the Union Constitution Committee, Provincial Constitution Committee, Union Powers Committee, and the Drafting Committee itself (1948)

Ambedkar shaped India’s monetary framework, fiscal federalism, labour protections, and constitutional architecture with a level of intellectual depth unmatched by most of his contemporaries.

At a time when India faces mass unemployment, informalisation of labour, shrinking worker protections, fiscal centralisation, and democratic strain, ignoring Ambedkar’s economic, legal, and labour thought is not accidental but politically convenient. To understand India’s present crisis and imagine a just future, Ambedkar must be read in full—not selectively, not symbolically, and not safely.

This series revisits three dimensions of Ambedkar that India has systematically ignored: Ambedkar the Economist, Ambedkar the Lawmaker, and Ambedkar the Labour Reformer.

Ambedkar, the Economist

India remembers Ambedkar as the architect of the Constitution and a fearless anti-caste revolutionary. These identities are central.

Yet confining him to them has buried one of the most critical aspects of his legacy: Ambedkar was one of the most accomplished economists this country has produced. At a moment of jobless growth, agrarian distress, extreme inequality, and fiscal centralisation, rediscovering Ambedkar the economist is not academic—it is essential.

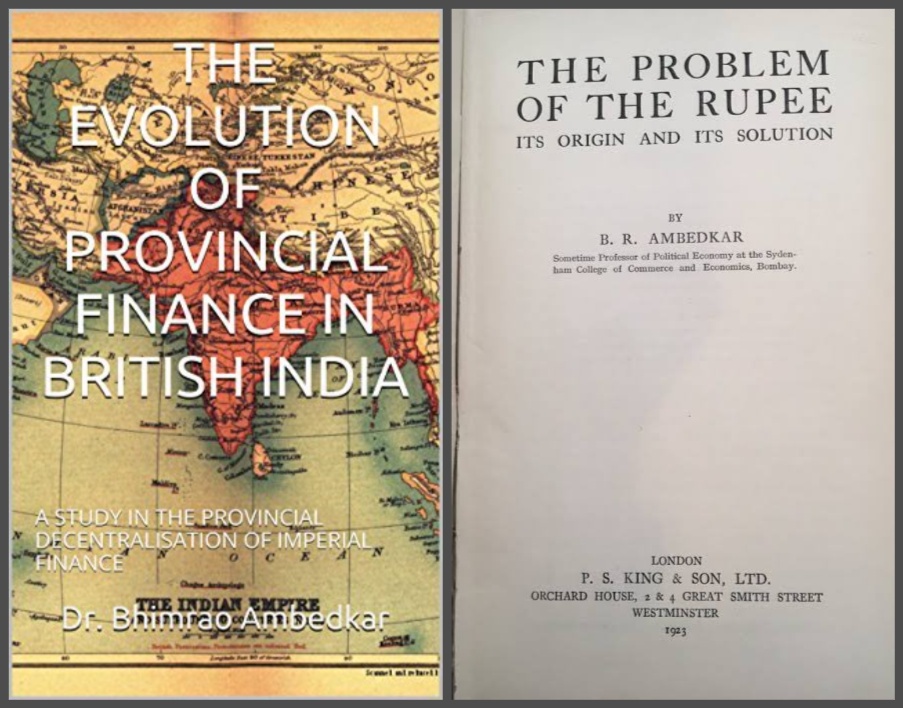

Ambedkar was the most rigorously trained economist among India’s national leaders. He earned a Master's in Economics from Columbia University in 1915, a doctorate in 1917 for The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India, and a Doctor of Science (DSc) from the London School of Economics in 1923 for The Problem of the Rupee.

Trained under Edwin R.A. Seligman, a founder of modern public finance, Ambedkar developed expertise in fiscal federalism, monetary policy, labour economics, and political economy. These were not ornamental degrees; they shaped the economic architecture of modern India.

His Columbia dissertation demonstrated how colonial rule weakened Indian provinces by centralising revenue while decentralising expenditure. Ambedkar argued that democracy could not survive without fiscal autonomy for provinces and local governments.

Long before “cooperative federalism” entered the political vocabulary, Ambedkar warned that political democracy without economic decentralisation would hollow out self-rule.

At the LSE, Ambedkar’s work on currency rejected the exploitative Gold Exchange Standard and proposed a scientifically managed monetary system. Many of his recommendations directly influenced the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934.

Ambedkar was not merely theorising—he was designing institutions.

His economic imagination extended to infrastructure and natural resources. As a member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, Ambedkar conceptualised multi-purpose river valley projects such as the Damodar Valley Corporation and major dams like Hirakud, Koyna, and Sone.

Image: Ambedkar talking to people as the Labour Member in the Viceroy's Executive Council at the coal mines in Dhanbad (left); photo source - Dr B R Ambedkar's Caravan, and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru inaugurating the Damodar Valley Corporation (right)

Ambedkar viewed water not as a cultural symbol but as an economic resource critical to agriculture, electricity, flood control, and industrialisation—ideas that resonate sharply amid today’s climate crisis.

Land and agrarian relations occupied a central place in Ambedkar’s economic thought. He argued that caste oppression was inseparable from land monopoly. Without redistributing land and dismantling landlord dominance, social equality would remain a legal fiction.

Ambedkar proposed state regulation or ownership of land, cooperative farming, and scientific agriculture. For Ambedkar, economic democracy demanded redistribution—not merely formal rights.

In States and Minorities (1947), Ambedkar articulated a model of democratic state socialism: public ownership of key industries, restrictions on wealth concentration, constitutional protection of labour rights, and democratic accountability. It was neither Soviet authoritarianism nor laissez-faire capitalism, but a welfare state remarkably aligned with later Scandinavian models.

Yet India has systematically erased Ambedkar the economist from its public consciousness and policy discourses. The dominant-caste academia prefers a symbolic Dalit icon over an economist who interrogated capital, caste, and state power.

Centralising elites found his federalism inconvenient. Hindutva politics frames him as anti-Hindu rather than engaging with his structural critique of inequality. The cost of this erasure is visible today: mass unemployment, stagnant wages, agrarian collapse, corporate concentration, and the informalisation of labour.

Ambedkar warned that political democracy cannot survive without economic democracy. Ignoring him has not made India stronger—it has made it fragile.

To read Ambedkar as an economist is to recover a blueprint for fair federalism, labour-centred growth, and social democracy. He was not only fighting for dignity; he was designing justice.

India urgently needs that Ambedkar today.

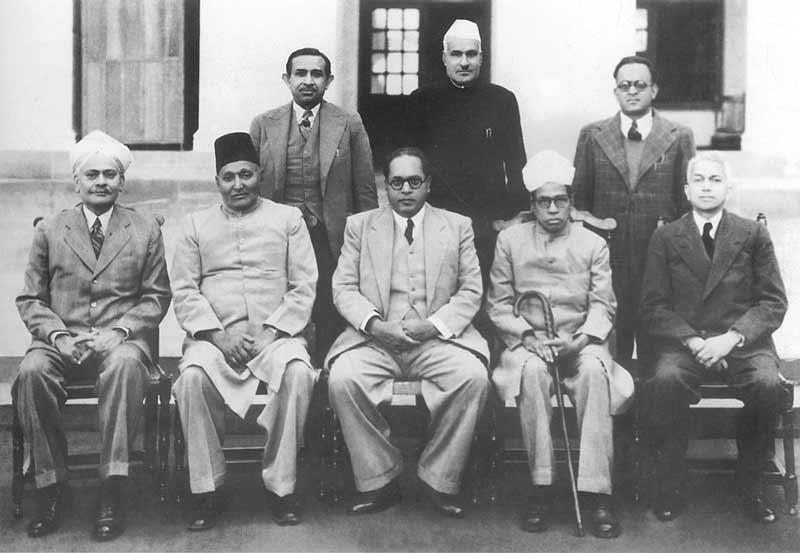

Image: Members of the Drafting Committee of the Constitution of India

Ambedkar, the Lawmaker

Ambedkar is often remembered as a Dalit icon or constitutional draftsman. Both descriptions are true—and insufficient. Ambedkar was one of the greatest legal minds India has produced: a barrister trained at Gray’s Inn, a comparative constitutional scholar, a courtroom advocate, and a jurist whose legal imagination shaped the Indian republic.

Ambedkar’s legal education was global and rigorous. At Gray’s Inn and the London School of Economics, he studied jurisprudence, constitutional law, international law, and comparative political systems.

He examined the constitutional frameworks of the United States, Canada, Australia, Ireland, South Africa, and Europe. This depth of comparative literacy distinguished him from all other nationalist leaders of his time.

Returning to India, Ambedkar practised at the Bombay High Court, representing marginalised communities in land disputes, public-access cases, and labour conflicts. He invoked evolving international labour standards and constitutional principles even before India had a constitution. His legal work consistently linked law to social power.

Image: Ambedkar, along with Mahatma Gandhi, attended the Round Table Conferences in London (1930-31); photo source - Navayan

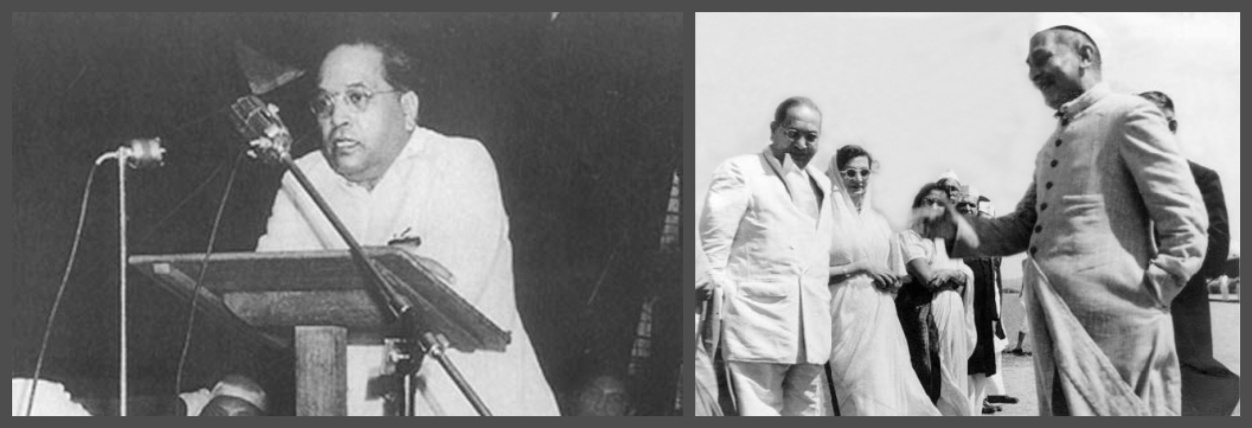

At the Round Table Conferences, Ambedkar articulated one of the most sophisticated minority-rights arguments of the twentieth century. He insisted that democracy without safeguards for oppressed communities was tyranny.

Political equality without social equality, he argued, merely reproduced domination. These arguments shaped the Communal Award and later the constitutional logic of reservations—not as charity, but as democratic necessity.

As Labour Member in the Viceroy’s Executive Council (1942–46), Ambedkar’s legislative interventions transformed the colonial labour laws. He piloted amendments to the Factories Act, the Minimum Wages Bill, maternity benefits, trade union recognition, employment exchanges, and protections for mine, dock, and railway workers.

These reforms were grounded in comparative labour jurisprudence and constitutional reasoning.

His most radical legal intervention—the Hindu Code Bill—nearly cost him his political career. Ambedkar sought to codify gender equality in property, marriage, divorce, and inheritance. When the Bill faced resistance from conservative forces and political hesitation, Ambedkar resigned from the Cabinet.

Modern Hindu personal law rests on his unfinished work.

As Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Constitution of India, Ambedkar synthesised global constitutional principles into an Indian framework that balanced rights, federalism, parliamentary democracy, judicial review, and institutional independence. His warning remains prescient: constitutional morality must be cultivated, not assumed.

Reducing Ambedkar to a caste symbol erases his legal challenge to social hierarchy and state power. At a time of majoritarianism, weakened institutions, and executive centralisation, Ambedkar’s jurisprudence remains India’s strongest democratic safeguard.

Image: Addressing the Constituent Assembly (left), with President Dr Rajendra Prasad (right)

Ambedkar, the Labour Reformer

Ambedkar was not only a constitutionalist or economist; he was one of India’s greatest labour-rights reformers. A labour economist by training, a union organiser by practice, and India’s first national labour architect, Ambedkar built the foundation of worker protections that still exist today.

His engagement with labour began early, shaped by empirical study and lived realities. In Bombay, he organised textile workers, formed labour associations, and used Mook Nayak and Bahishkrit Bharat to expose industrial exploitation.

His Independent Labour Party, founded in 1936, placed labour rights at the centre of political struggle—linking caste, class, and economic power.

Ambedkar understood caste as an economic structure that segmented labour and depressed wages. Movements like the Mahad satyagraha were not merely symbolic—they were struggles for material survival. Access to water, housing, and public resources was central to labour dignity.

As a Labour Member from 1942 to 1946, Ambedkar institutionalised labour rights at an unprecedented scale. He introduced the eight-hour workday, maternity benefits, minimum wages, compensation for workplace injuries, provident fund frameworks, employment exchanges, and trade union recognition.

Image: Ambedkar with members of the Independent Labour Party, which he helped found in 1936

In four years, he created the skeleton of India’s labour protections.

Ambedkar embedded labour rights into the Constitution itself. Articles abolishing untouchability, prohibiting forced and child labour, ensuring equality in employment, and guaranteeing humane working conditions reflect his conviction that democracy collapses without worker security.

The Directive Principles envision living wages, social security, and worker participation in management.

A legacy that cannot be erased

Ambedkar warned repeatedly that political democracy without economic democracy is unsustainable. Today’s informalisation, dilution of labour laws, and gig-economy precarity confirm his fears. The erasure of Ambedkar, the labour reformer, has left India intellectually unarmed in confronting these crises.

To reclaim Ambedkar is to reclaim labour justice as the foundation of democracy.

India can no longer afford to remember Ambedkar selectively. To confront today’s crises—joblessness, informal labour, fiscal imbalance, and democratic erosion—we must reclaim Ambedkar the Economist, Ambedkar the Lawmaker, and Ambedkar the Labour Reformer together.

His ideas offer not nostalgia, but tools – for economic justice, constitutional morality, and social democracy. Rediscovering Ambedkar in full is not an intellectual exercise; it is a political necessity.

(Views expressed in this report are the author's own.)

Follow us on WhatsApp

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X @vudmedia

Follow us on Substack