03 March 2026

The Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum accounts for 60 per cent of global GDP, and stretches from the Western hemisphere to the East along the Pacific Rim. Yet, despite being one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, India is not a member of this forum, which guides the norms and rules for the world’s consequential economic partnerships. The reasons for the world’s fourth-largest economy remaining outside the APEC are a result of historical hangovers and aberrations, as Professor Swaran Singh points out in this 10th edition of Asia Watch, in which he explains why India's integration with the APEC will be a win-win for both.

Banner Image: World leaders at the APEC 2010 in Japan

Home image: World leaders at the APEC 2024 in Peru

The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum — which is having its 32nd summit in South Korea this Friday — was founded in 1989 to promote free trade and investments among Pacific-rim economies. Today, 21 members of APEC account for 60 per cent of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and half of world trade.

Significantly, it includes the world’s two largest economies – the United States and China. This makes APEC the world’s most consequential ‘informal’ club that charts much of the normative structures and rule-making that goes into designing the world’s key economic partnerships.

Yet, quite paradoxically, India, which is the world’s fourth largest as well as the fastest-growing amongst major economies, remains an outlier. This is despite the fact that India is also now recognised as a major stakeholder in the evolving Indo-Pacific paradigm.

Image: The Hwabaek International Convention Centre (HICO) in Gyeongju, the venue of the APEC Summit later this week

Since 2007, India has been an influential member of the Indo-Pacific ‘Quad’ and, from May 2022, a founding member of the 14-member Indo-Pacific Economic Forum for Prosperity. After joining the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) as its Sectoral Partner in 1992, India became the founding member of the East Asia Summit in 2005, whereas even the US and Russia took a full decade to join the Summit by 2015.

Why is India an outlier?

To begin with, does this omission of India in APEC matters? Annual APEC summits are usually the time when the commentariat raises such questions as to why India has not joined this forum despite its close cultural ties with several of these societies.

Indeed, India has usually not been on their target screen.

The stock answer one gets is that, way back in 1997, APEC had put a freeze on accepting new members, and that this moratorium, plus China’s quiet opposition, had kept India outside this forum. But India had formally applied for its membership way before – in 1991 and then in 1997.

To that, the answer is that during the 1990s, India was not seen as part of the Pacific-Asia, which was limited to Japan and its ‘tiger’ economies of Southeast Asia, with China barely putting a foot in the door for its inordinately high economic growth rates during the early 1990s. Others allude to the 2019 instance when India had walked out of the 16-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Cooperation.

The reality is that, other than being invited to a couple of observer dialogues and as a ‘guest economy’ in 2014 and 2023, India is not a member of APEC. Indeed, this is not even in discussion at any of the meetings of APEC, including their summit this week.

Prima facie, this negation of India seems at odds with India’s self-image of expanding engagement with the Indo-Pacific. From an Indian perspective, this negation raises the question whether India’s non-membership of APEC marks a symptom of some deeper malaise and whether it has caused any strategic constraint on India’s Act East and Indo-Pacific policies.

Especially, in the face of the ever-growing US-China tensions, it also begs the question if India’s entry into APEC can, in any way, contribute to APEC’s effort at building synergies. Such contributions seem so badly needed amidst the tariff turmoil triggered by US President Donald Trump. The resultant volatilities call for the recasting of regional supply chains and measures to stabilise the larger regional trade?governance structures that seem to be on a precipice.

Conversely, does India’s non-membership reflect the APEC’s historical, structural, normative or geopolitical impediments? If so, how can India’s future inclusion (or continued absence) impact APEC’s future trajectories?

First, what does APEC stand for?

First and foremost, it is important to underline that APEC operates on the principle of ‘open regionalism,’ which implies an element of flexibility, especially to co-opt new stakeholders. The current APEC itself spans from North America to Latin America, East Asia, Southeast Asia and Oceania.

Ideationally as well, APEC endorses voluntary liberalisation via annual Leaders’ Meetings, Senior Officials Meetings, and a network of working groups. Given India’s transformation since the 1990s, this should make India’s absence at APEC a conspicuous missing link.

Image: APEC Finance Ministers meeting in Incheon, South Korea, in the run up to the Heads of State Summit

Second, APEC serves as a norm-shaping forum. The ‘Bogor Goals’ adopted in 1994 sought to commit its members to free and open trade as well as investments by reducing tariffs between zero to five percent, with its industrialised economies expected to meet this requirement by 2010 and the developing economies by 2020. This staggered approach should have well accommodated India’s increasing focus on Free Trade Arrangements and digitalisation.

Nonetheless, such lofty goals of APEC have no binding powers of treaties. Most APEC decisions are driven by its consensual mechanism and peer-review processes that seek to influence agendas on trade governance, digital economy norms, supply-chain resilience frameworks and connectivity.

Third, APEC provides a strategic space where major powers (notably the United States, China, Japan, South Korea, and Australia) engage in multilateral economic diplomacy that often spills over into security and strategic realms. In other words, bilateral meetings on the sidelines of APEC often provide windows of strategic stabilisation or even reset opportunities. The APEC forum’s focus on issues beyond economics and emerging as a platform for voluntary coordination in the contested Indo-Pacific geopolitics also makes India a perfect fit to join it.

Finally, while the inclusion of the rapidly growing economy of India promises to make APEC far more representative and perhaps even a more credible forum, India also stands to gain, which makes it a win-win formulation.

What then explains India not even being on their radar screen?

Structural, normative and geopolitical reasons

Let us first look at the APEC’s moratorium on membership and its dated sense of physical geographies.

It was in the wake of its economic reforms of the early 1990s that India first expressed interest in joining APEC in 1991. Clearly, India was not seen as part of the imaginations of the Pacific-Asia then, that was being crafted around the Japan-led ‘tiger’ economies of Southeast Asia, with China just managing to become accepted. The explanation was that India did not have a Pacific coastline and did not meet the APEC’s geographic logic.

Second, also from the early 1990s, India’s Look East policy had just begun exploring partnerships in the East while its trading relations were still constrained by the ‘permit raj’ of its ‘socialist’ era. A recurring objection within APEC circles cited India’s historically cautious trade posture, protectionism, and its record in WTO negotiations.

The annual report of the Asia Society Policy Institute, as late as 2016, had argued that India would need to demonstrate a sustained commitment to liberal economic integration before its full APEC membership was even considered.

Third, given the baggage of three India-Pakistan wars plus the implosion of Pakistan-sponsored terrorism from the late 1980s, India’s entry into APEC was seen as having the potential to disrupt its intra-regional equilibria. Some existing members feared that Indian membership could tilt the forum’s dynamics by the weight of South Asia’s labour-intensive economies or alter the focus of supply chains.

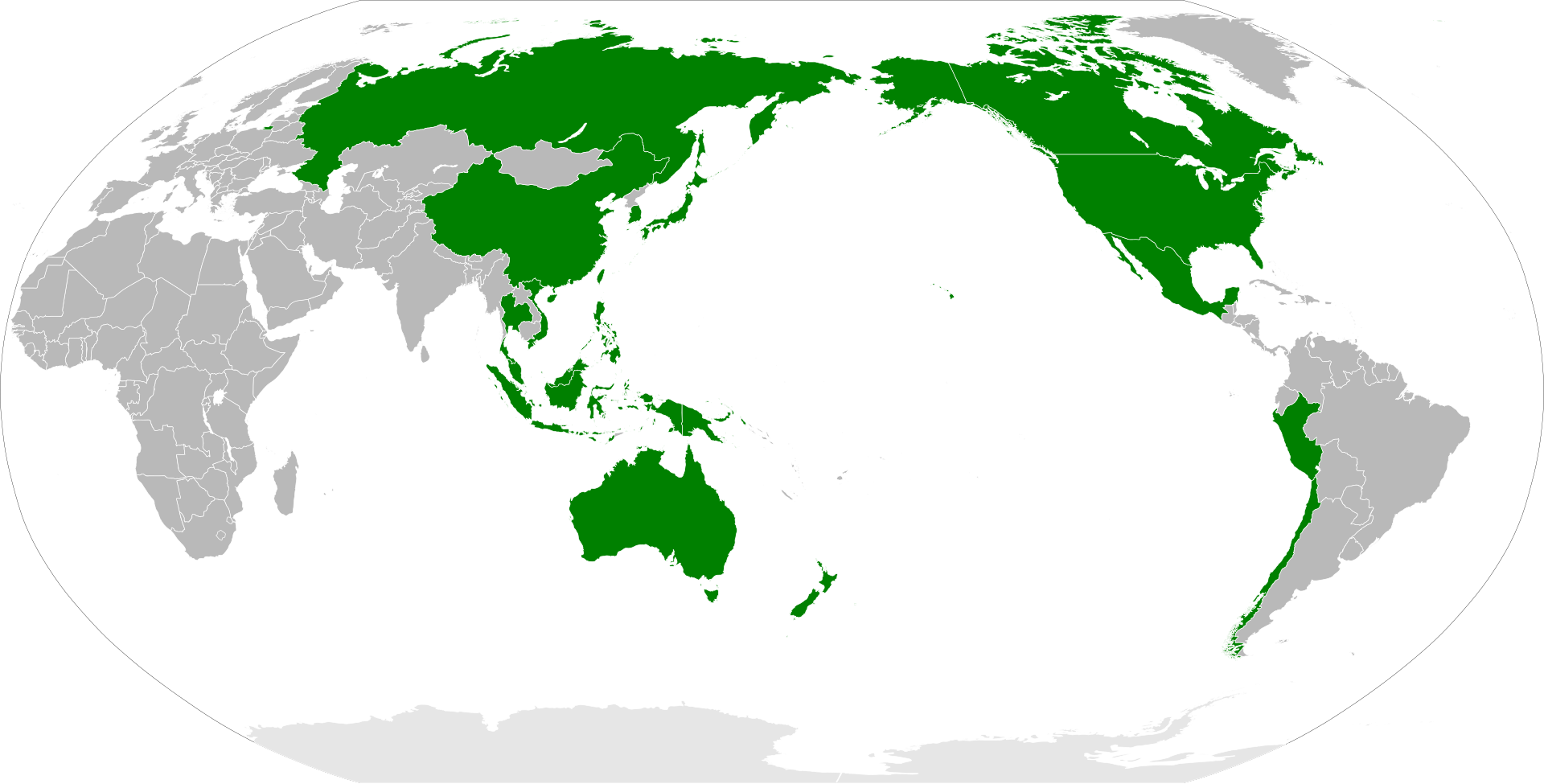

Image: The map showing APEC member states

Image: The map showing APEC member states

Similarly, given India’s complex relationship with China, some APEC members viewed India’s inclusion as likely to inject added strategic tension into this informal club of select economies.

Fourth, though India’s domestic reform rhythm and external engagements had begun from the 1990s, these were still to earn trust and credibility. While India’s economy has since grown impressively — with average GDP growth preceding the COVID-19 pandemic often exceeding 7 per cent — its external trade orientation has only gradually shifted from an inward to an outward-looking approach.

But India’s past reluctance to integrate into East Asian production networks kept this Asian giant on the periphery of the ‘flying geese’ export-driven development cluster.

Finally, there have also been other aspirants from the Pacific rim itself, while India has not had a clear, singular champion within APEC for its membership. This institutional competition has meant that India’s application has remained pending despite repeated expressions of interest.

Why should India join the APEC?

The question is relevant as to why India should be pushing to join the grouping if the APEC does not show any clear interest? There are compelling arguments for why India’s accession to APEC will be a strategic win for both sides.

First, India’s share of trade with APEC economies already stands at roughly 40 percent of India’s total foreign trade. Yet, many Indian firms are on the margins of East and Southeast Asian production networks. Joining APEC would offer institutional access to regional working groups, regulatory dialogues and supply-chain resilience frameworks, thereby enabling the ‘Make in India’ project to link deeper into the larger regional production networks.

Second, APEC’s voluntary liberalisation processes, peer review and capacity?building mechanisms can offer India a platform to better integrate with 21st-century trade governance — digital economy, services liberalisation, investment facilitation — without the shocks of a large comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (FTA).

Thereby, India’s inclusion would improve APEC’s representativeness and reflect an inclusive approach that could ensure regional stability.

Third, India’s membership would drive home the message that India is no longer an economic ‘outsider’ in the Indo-Pacific economic architecture but an integrated actor. It would further strengthen India’s Act East policy and buttress its role in the Indo-Pacific mosaic alongside the Quad, IPEF and the ASEAN plus frameworks.

Why has India not joined so far?

APEC has hinted a few times at India’s domestic liberalisation imperative and expects it to continue to demonstrate ‘institutional reforms,’ which include lowering tariffs, clearer investment regimes, liberalisation of services, alignment with global digital and data frameworks, and so on.

Second, India’s strategic diplomacy needs to secure on its side a few championing states within the APEC to build a consensus in its favour. Reports highlight early support from the US, Australia, South Korea and Papua New Guinea. However, India must craft a clear accession strategy and a need to put sustained efforts into it.

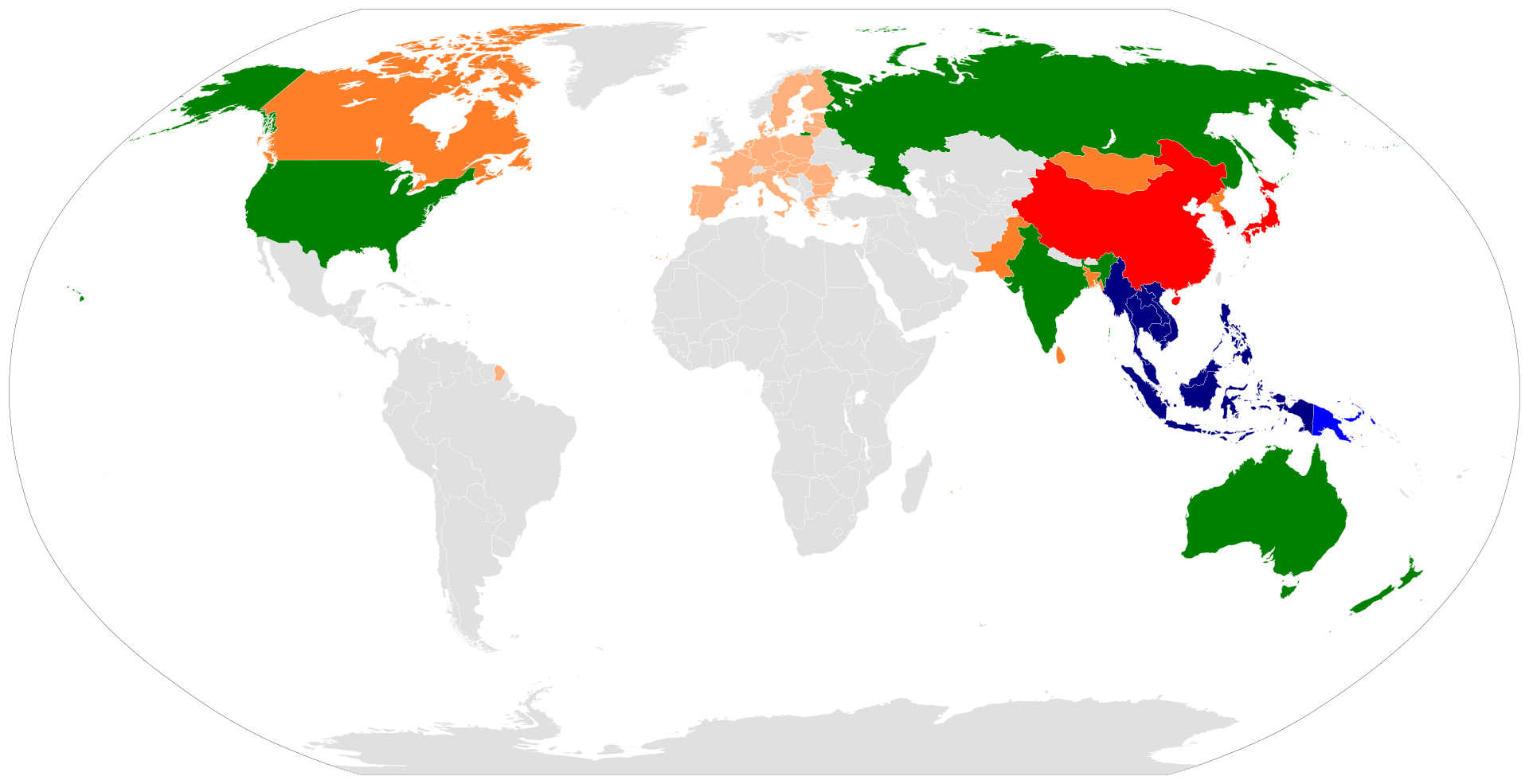

Image: The map of ASEAN full-member states, observer states, ASEAN+3, East Asia Summit members and ASEAN Regional Forum

Third, India will have to address the objections around the Pacific-rim geographical criterion. This could be done by emphasising India’s trade and maritime linkages across the Indian and the Pacific oceans and front-loading of its Indo-Pacific strategy. This should make India a better fit for the APEC architecture.

Finally, while the APEC’s moratorium on new members officially ended in 2012, no new additions have been accepted so far. India can align its accession timing with potential institutional reforms in APEC to accept new members, as well as to build new regional realignments that reflect the changed realities of the decade.

What APEC means for India’s Indo-Pacific strategy

From a strategic standpoint for India’s Indo-Pacific policy, the absence from APEC carries a range of missed opportunities.

First, many littoral economies of the Pacific are deeply networked through the APEC’s working groups, regulatory dialogues, and cross-border frameworks. India, being outside this network, faces informational and normative lag – be it regulatory standards, digital trade norms or the supply-chain resilience mechanisms that are developed within the APEC.

India, thus, risks being a late follower rather than a co-creator.

Second, without a seat at the high table, India cannot shape the agendas that mould regional economic and strategic interests. These include, for instance, norms on semiconductors, rare-earths, digital trade, or regional connectivity. Given the US-China rivalry, these are precisely the domains where economic governance intersects strategic competition.

Third, while India was once active in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) (before opting out) and the Indo?Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), neither replicates the multilateral breadth or institutional depth of the APEC.

Finally, from a geopolitical perspective, joining the APEC would underscore India’s willingness to integrate economically with the Indo-Pacific rather than remain peripheral. Non-membership leaves India outside a major economic-security architecture and, thus, somewhat marginalised.

What to watch for in the future?

Will India join APEC? The prospects are cautiously optimistic and conditional.

The possible pathways could include India aligning its accession bid with broader institutional reform in the APEC. The other approach could be to demonstrate continued trade and regulatory alignment that could ensure accession in the next 5 to 10 years. This could make APEC membership a catalyst as also a consequence of India becoming third third-largest economy by that time.

The APEC, in the meantime, might also evolve new formats of inviting aspirant nations, as dialogue partners or observers, etc.

Key trends to watch could include:

- Whether India will submit a formal renewed application for the APEC membership and start accession negotiations;

- Whether India’s ‘Quad’ allies and China will have reason to coalesce around India’s entry;

- Whether India’s deeper economic reforms will meet the expectations of APEC sheriffs.

Image: A map showing RCEP member states (right) and their trade share (left)

India’s deepening engagement with the APEC economies through technical dialogues, observer status, and Track-II dialogues could also build familiarity and goodwill.

Should India succeed in joining APEC, the benefits would be substantial and for both sides. India may access regional economic governance, deeper supply-chain integration, greater strategic heft in the Indo-Pacific, and improved innovation/digital integration with regional economies.

If India remains outside, it will continue to engage bilaterally and through other frameworks, but will risk missing the institutional momentum that APEC offers.

APEC integral to ‘Viksit Bharat’

APEC, therefore, remains a critical and a yet-to-be-utilised architecture for India’s Indo-Pacific strategy. The fact that India remains outside this powerful regional forum is not simply a historical anomaly; it reflects deep structural, normative and strategic disjunctures.

Yet, the logic of India’s accession is now stronger than ever: the region’s economic gravity is shifting, supply-chain realignments are underway, and strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific demands inclusive economic partnerships.

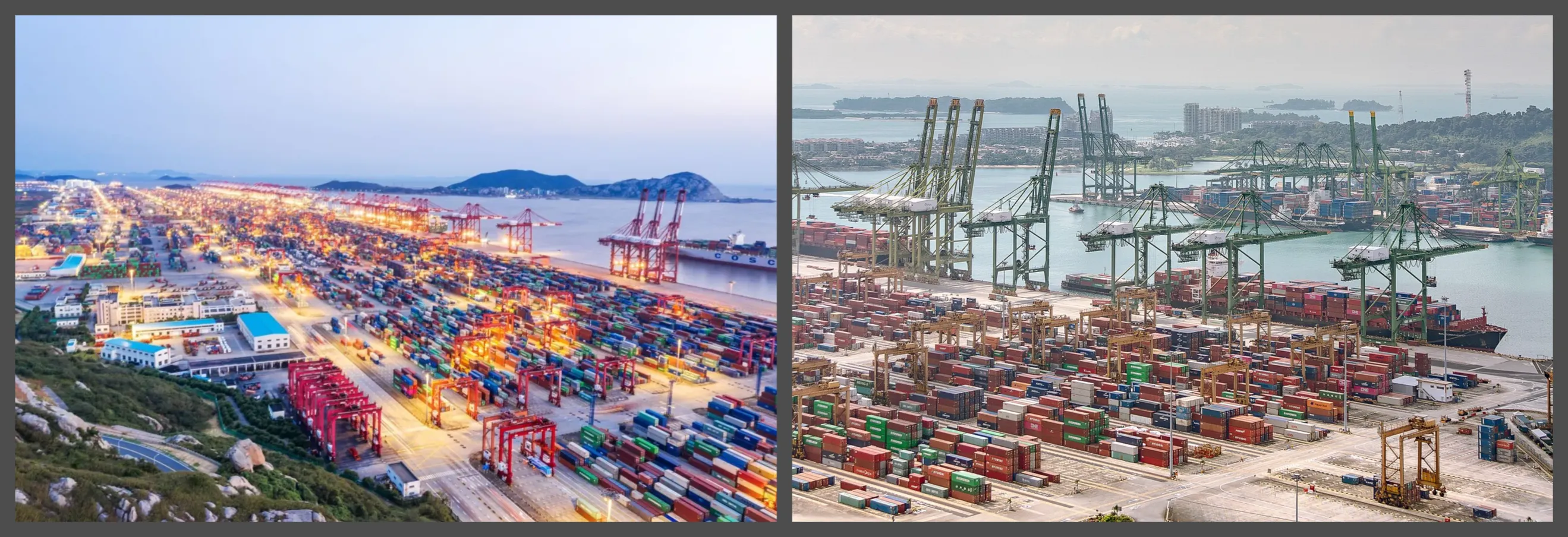

Image: The Ports of Shanghai (left) and Singapore (right), which are among the largest ports in the Indo-Pacific region.

Image: The Ports of Shanghai (left) and Singapore (right), which are among the largest ports in the Indo-Pacific region.

India’s membership of APEC would, thus, mark the completion of its institutional integration into the Indo-Pacific economic order, something that its Act East and Indo-Pacific policies implicitly aspire to, but have not yet fully achieved. However, realistically speaking, even a most optimistic prognosis of such a possibility will show that India’s accession to APEC will need sustained, focused and patient efforts and time.

Staying out of APEC is not a choice if the ‘Viksit Bharat’ vision has to fructify.

Follow us on WhatsApp

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X @vudmedia