22 January 2026

In the magnificent Kim Il-sung Square of Pyongyang this Friday, contingents of military personnel and rocketry will march down to mark the 80th anniversary of the Workers’ Party of Korea. To assume that a communist party, run by the Kim dynasty, has survived as the last vestige of the Second World War, 80 years later, in itself denotes not just political resilience but also ideological endurance and institutional elasticity. The festivities, expectedly, will not just witness a show of military might, but also a form of geopolitical confidence which few small states can brandish, as North Korea could, in the company of its Asian socialist compatriots – China, Russia and Vietnam, says Professor Swaran Singh in this 9th edition of the Asia Watch.

Text page image: The monument to the WPK founding erected in Pyongyang in 1995. Photo credit: Nicor

Home image: The Mansudae Grand Monument in Pyongyang for Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-iI. Photo credit: J.A. de Roo

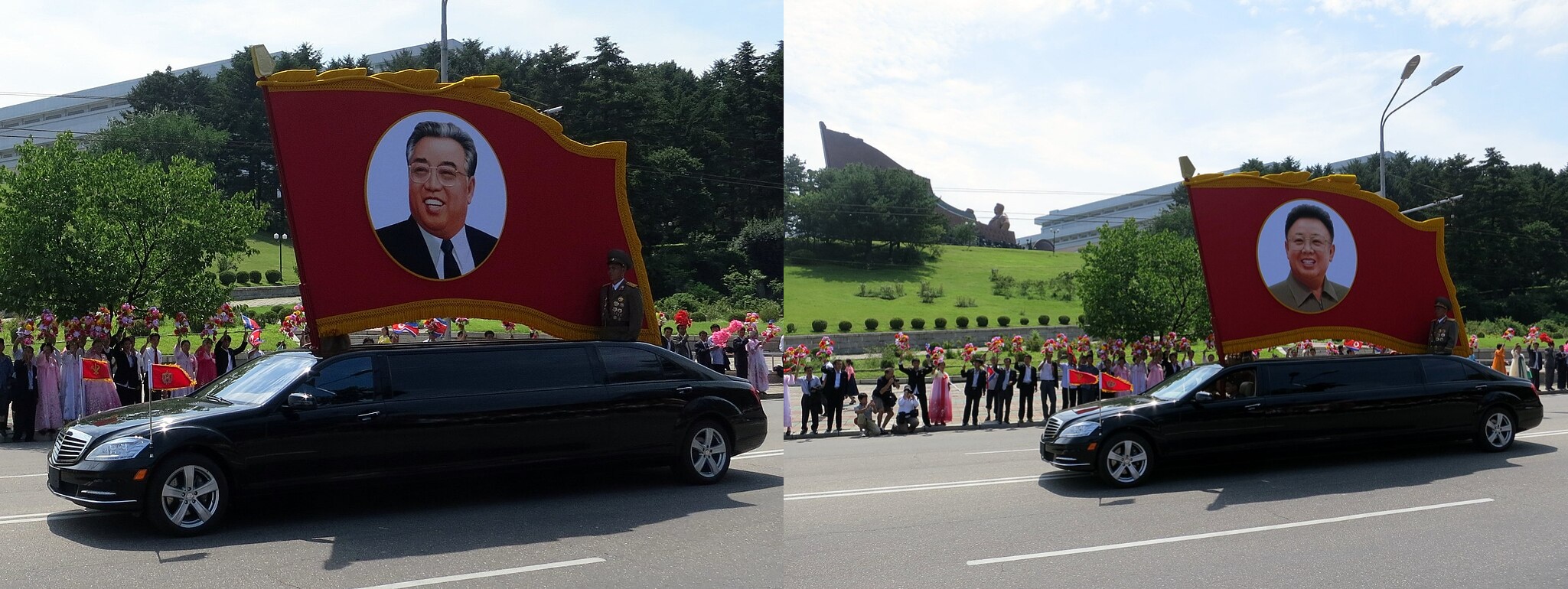

Banner image: WPK cadre at the 100th birthday celebrations of Kim Il-sung in 2012. Photo credit: Joseph Ferris III

As fireworks illuminate Pyongyang’s skyline this week, North Korea’s capital is not just celebrating history — it is reasserting defiance in international politics. The 80th anniversary of the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) this Friday is, therefore, not a mere political ritual; it is a statement of survival, sovereignty, and strategic insight that makes North Korea a player in the fast-changing global geopolitics.

From October 9 to 11, delegations from China, Russia, and Vietnam are converging on this ‘hermit kingdom,’ with China’s Premier Li Qiang leading Beijing’s team, and Russia’s Dmitry Medvedev representing the Kremlin. Their presence will also mark their highest-level visits to Pyongyang in six years.

This usual spectacle culminates on October 10th, when a typically hysterical massive military parade will be rolled out, once again, through the Kim Il-sung Square, brandishing not only tanks and missiles but also North Korea’s renewed geopolitical confidence.

Image: Portraits of Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il and Kim Jong-un

Beyond being symbolic, the WPK will use these celebrations to signal its claim to being back at the centre of great-power politics, sitting astride the tightening of what the European Union’s foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas calls the ‘autocratic alliance’ of Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-un.

Indisputably, this is an axis that seems to be reshaping the balance of power across East Asia, if not beyond.

The Party that outlasted history

Despite persistent Western complaints and criticisms about the singularity and style of North Korea’s WPK, few ruling parties in the annals of modern political history have shown such ideological endurance and institutional elasticity.

Even the Chinese Communist Party, which has survived for 104 years, has had a much tumultuous history of being led, not by one family, but by leaders who dissented, got purged, or simply vanished with the change of leadership.

Founded on 10 October 1945 under Soviet oversight, the Workers’ Party began as a Soviet provincial branch of the Korean communists. And yet, through war, famine, and international ostracism, it persisted with its dynastic power structure unparalleled in the socialist world.

Handpicked by Joseph Stalin and made head of the Provisional People’s Committee of North Korea in February 1946, following the Second World War, Kim Il-sung had soon purged all his rival factions and consolidated his Party’s absolute control on North Korean politics.

Image: The founding joint plenum of the New Peoples’ Party and the North Korea Bureau of the Communist Party of Korea on 28 August 1946. Photo credit: Wikipedia

The 6th Party Congress (1980) was to elevate his son Kim Jong-il, institutionalising hereditary succession — an unheard of innovation in communist systems. Even when the Soviet Union disintegrated and North Korea faced a devastating famine in the early 1990s, the WPK survived by reinterpreting the crisis in terms of its ideology: Songun, or ‘military-first’ politics, turning its armed forces into both shield and sanctuary for its leadership.

When the grandson, Kim Jong-un, inherited the mantle in 2011, predictions of collapse were legion. Yet, instead of implosion, came consolidation. Allegedly, he executed over a dozen senior military officials in 2012. Kim Jong-un revived the Party’s primacy over the military, modernised its propaganda machine, and entrenched nuclear deterrence as the regime’s existential guarantee.

The 7th (2016) and 8th (2021) Party Congresses canonised nuclear weapons as ‘eternal,’ while reasserting the mantra of ‘self-reliance under pressure.’ At eighty, the WPK has turned survival into a strategy and isolation into exclusivity.

Pageantry with a purpose

Pyongyang’s anniversary festivities are likely to be more than an exercise in nostalgia about revolutionary history. These are expected to showcase a theatre of its new role in the emerging geopolitical choreography.

Image: A party congress in session and a memorial for the Korean War

The parade of October 10th, expected to begin at dusk, is likely to flaunt North Korea’s latest hypersonic and submarine-launched missiles, alongside legions of troops marching in near-perfect unison — a carefully staged display of military modernity and political continuity.

Cultural galas, mass games, and fireworks will aim to amplify the message that WPK is not merely celebrating its past — it is broadcasting its place in the future of world politics. Some of that drama is already unfolding off the parade grounds. Premier Li Qiang, expected to arrive on October 9th, signals Beijing’s reaffirmation of fraternity with its unpredictable neighbour.

For China, North Korea remains both a buffer and a bargaining chip — a shield against US power on the peninsula and a pressure point in its regional strategy. For Pyongyang, China is a lifeline and leverage rolled into one: aid provider, trade artery, and diplomatic cover at the UN Security Council.

Simultaneously, Pyongyang’s growing intimacy with Moscow is rewriting this curious calculus of regional geopolitics. Kim Jong-un’s dispatch of 10,000 troops to Russia’s war in Ukraine is a dramatic show of solidarity — and audacity! The presence of Dmitry Medvedev at the celebrations underscores that Russia, too, sees value in embracing a fellow sanctioned state — one that can supply manpower, munitions, and legitimacy to its anti-Western narrative.

For both Beijing and Moscow, North Korea has become a small state with a heavy strategic punch — a partner that defies Western containment while deepening multipolar momentum for Moscow and Beijing. The addition of Vietnam’s Communist Party chief To Lam completes the tableau, representing Asia’s last surviving socialist quartet standing shoulder to shoulder in Pyongyang.

Why the world cannot look away

North Korea is easy to caricature as a nuclear-armed autocracy, frozen in time. But that simplification misses the point. The WPK’s 80th anniversary is a lens into the political durability and strategic relevance of a state that refuses to fit the dominant or mainstream post-Cold War script.

1. A living relic of the Cold War

While most socialist states crumbled after 1989, North Korea remained intact — not only a living fossil of the Cold War, but also a reminder that the post-World War II ideological competition never truly vanished. Even the Chinese had to adopt a Socialist Free Market Economy model and allow private ownership for its citizens.

North Korea’s political machinery, ideological orthodoxy, and cultic leadership represent an extreme case of regime resilience — where isolation is not a weakness but an organising principle of legitimacy. Regime change strategies have failed to deliver in this case.

2. An asymmetric deterrence lab

Since its first nuclear test in August 2006, North Korea has forced strategists to rethink deterrence theory. It not only turned into an inspiration for aspirant states to acquire nuclear weapons but also benefited from nuclear and missile technology collaborations with Russia, China, Pakistan, Iran, Syria, Myanmar, Libya, and so on.

Pyongyang, however, wields atomic capability not for aggression or nuclear deterrence the way we know. Rather, the capability seems to be for regime endurance or what Kim Jong-un calls ‘Byungjin Line’ from 2013 — converting vulnerability into deterrence, sanctions into self-reliance, and provocation into negotiation leverages.

Image: A missile on display at the 70th anniversary parade. Photo credit: Stefen Krasowski

In this sense, Pyongyang is not an outlier but a prototype for the small nuclear state of the 21st century.

3. A pivot between empires

Wedged between China, Russia, Japan and South Korea, the Korean Peninsula remains the fault line of Asian geopolitics. North Korea’s choices — whether missile launches or diplomatic overtures — reverberate across every regional capital, shaping the military posture of all four powers and complicating US strategy in the Indo-Pacific region.

Lately, Kim Jong-un has been holding parleys with both President Vladimir Putin and President Xi Jinping. Earlier, the first term of President Trump had seen him holding three meetings with Kim in just over two years. So much so that his ever-expanding international engagements have made him less focused on inter-Korean anxieties.

4. A symbol of defiance in the Global South

In much of the developing world, Pyongyang’s survival story perhaps carries strong emotional resonance. Its continued defiance of sanctions and regime-change threats is seen, howsoever problematically, as a metaphor for resistance to Western hegemony.

The WPK’s slogans of sovereignty and self-reliance echo in the rhetoric of other states seeking policy autonomy amid polarised geopolitics.

5. The grandmaster of diplomatic theatre

From the Trump–Kim summits to sudden olive branches to Seoul, Pyongyang has mastered the art of crisis diplomacy — manufacturing tension to gain relevance, then using that relevance to gain concessions.

Image: Kim Jong-un with Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping

Few small states have so consistently outplayed their size and stature in global politics.

Xi–Putin–Kim: A new strategic geometry

In this context, the simultaneous presence of Li Qiang, Medvedev, and To Lam in Pyongyang marks more than solidarity — it signals a realignment of so-called authoritarian diplomacy in an increasingly unstable and fragmented world politics.

- For China, North Korea remains both an asset and a risk. Beijing cannot afford chaos on its border, nor can it allow Washington to dominate the peninsula. Hence, Li’s visit reaffirms China’s strategy of managing Pyongyang through proximity, not pressure.

- For Russia, deepening engagement offers both symbolic and practical gains. North Korean munitions, manpower, and ideological kinship reinforce Moscow’s defiance of Western sanctions while extending its influence into East Asia.

- For North Korea, balancing the two giants is the key. Other than finding access to Russian technology and Chinese finance and energy, Kim Jong-un’s recent leaning toward Moscow gives him room for manoeuvre vis-à-vis Beijing, ensuring that Pyongyang remains their partner, not a pawn.

This triangular diplomacy, in the midst of the newly minted ‘no-limit’ partnership of Moscow and Beijing, recalls the nostalgic Sino-Soviet alliance of the 1950s, with one twist: North Korea as the most agile player, exploiting great-power tensions to maximise its strategic opportunities.

Image: Kim Jong-un with President Donald Trump during their summit in Singapore

The Party that is the State

This 80th anniversary, therefore, is as much about ideology as about identity. The Workers’ Party of Korea is not merely the ruling party — it is the state. Its longevity rests on three interlocking pillars: dynastic legitimacy, ideological adaptation, and absolute control over the national narratives.

From Juche’s spiritual nationalism to Songun’s military primacy, and now to Kim Jong-un’s cautious techno-modernisation and nuclear deterrence, the Party has continuously reinvented itself without loosening its power grip.

This week’s perfectly choreographed parades and patriotic performances are thus more than pageantry. They are a performance of endurance — a public reaffirmation that the WPK, at 80, remains unbroken and unyielding.

No doubt, the WPK-led North Korea’s economy may have remained rather modest, its population small and less productive, and its diplomacy erratic — yet its global impact remains disproportionate, causing discomfiture to much of the Western world.

Every missile test rattles the global capitals, and every summit reshuffles regional alliances. In an age of renewed great-power rivalry, Pyongyang has come to be a strategic hinge between Eurasia and the Indo-Pacific, connecting two theatres of competition, often treated as separate.

For Washington and its allies, this means navigating a deterrence dilemma where China and Russia embolden Pyongyang. For Beijing and Moscow, it means leveraging North Korea as a geopolitical multiplier — a small partner that can unsettle larger adversaries.

Return of an unlikely power?

As the fireworks fade on October 10th, what will endure is the image of a state that refuses to vanish. Led by the Workers’ Party of Korea, which turns 80 this week, the North Korean state stands out both as a relic as also a revelation — a living embodiment of how ideology, isolation, and insecurity can combine into political obstinacy.

In a world once again dividing into competing blocs, North Korea can no longer be brushed aside as a forgotten legacy. It is a reminder that history’s outliers can often come to be its most disruptive catalyst, and that power, in the twenty-first century, is as much about persistence as prowess.

At 80, with all its problems, the WPK is not fading into history. It is perhaps rewriting it — in real time, under the floodlights of Pyongyang’s festivities.

Follow us on WhatsApp

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X @vudmedia