22 February 2026

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is headed to Israel this week for his second visit to the West Asian nation. While the visit will reflect his close friendship with the Israeli premier Benjamin Netanyahu, who has invited him to address the Knesset, the highlight of this visit will be the new frontiers of defence cooperation that are set to open up between the two countries. On the agenda is India’s quest for advanced interception technologies, including directed energy platforms, to propel its Mission Sudarshan Chakra even as New Delhi seeks to pursue a partnership for joint development, which, in turn, will help Tel Aviv break out of its traditional strategic mould. All these deliberations would, however, be with an eye on balancing the political dynamics in West Asia, points out Professor Swaran Singh in the 18th edition of Asia Watch.

Home page image: Prime Ministers Narendra Modi and Benjamin Netanyahu during the latter's visit to India in January 2018; photo source: PMO

Text page image: Flags of India and Israel atop a lamp post on Kartavya Path, photo credit: Wikipedia Commons

Banner image: An interceptor shoots off from an Iron Dome launcher; photo source - Rafael

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Israel later this week (25–26 February) may spark temptations to frame it as yet another milestone in India’s expanding global strategic outreach. Yet the real significance of this second trip lies not in novelty or optics, but in what it reveals about India’s evolving threat perceptions, defence priorities, and diplomatic risk-taking appetite.

This visit, therefore, will be low on symbolism and driven primarily by India’s cost-benefit analysis on Israel’s significance as a defence technology partner, amidst India’s increasingly complex security environment.

At the core of Prime Minister Modi’s agenda will be his Mission Sudarshan Chakra, an ambitious plan to develop a credible, multi-layered anti-ballistic missile defence (BMD) architecture to protect India’s hinterland against long-range missile strikes.

Israel, more than any other potential partner, offers operational experience, systems integration expertise, and a proven track record in missile interception. Whether this partnership can translate India’s ambitions into sustainable capability, however, remains an open and politically consequential question that calls for a serious scrutiny.

Missile defence at the centre stage

This missile defence-centric focus on Israel, first of all, reflects India’s changing strategic landscape, which guides its assessment of challenges and opportunities. Both Pakistan and China have continued to expand and diversify their nuclear and missile arsenals.

Both have invested in their longer ranges, manoeuvrable re-entry vehicles, hypersonic glide systems, enacting their saturation attack doctrines that could overwhelm India’s defence systems.

This threatens India’s traditional deterrence, when based solely on retaliation, and renders it insufficient, particularly in protecting its population centres, command nodes, and strategic infrastructure.

It is in this backdrop that Prime Minister Modi, during his Independence Day address from Red Fort last year, had enunciated Mission Sudarshan Chakra (epic signature weapon of Lord Krishna).

Aimed at protecting India’s critical establishments through indigenous technological development in the next ten years, the government plans to complete and deploy this nationwide security shield by 2035.

This implies moving India’s ongoing missile defence system from developmental stages to full-scale operational deployment. India’s indigenous BMD programme has demonstrated intercept capabilities in controlled tests, but scholars have long noted the ‘gap’ between technological demonstration and reliable, networked defence at scale.

Israel’s appeal for India lies precisely in having crossed that gap. Israel’s pioneering efforts and missile defence track record remain not just impressive but context-specific for India’s requirements.

Israel’s layered missile defence architecture — Arrow for long-range threats, David’s Sling for medium-range missiles, and Iron Dome for short-range rockets — has become the most combat-tested system of its kind.

Israel's layered BMD system: Arrow-2 (left), David's Sling (centre), and Iron Dome (right)

In the face of Iran’s massive strikes of 550 missiles and 1,000 plus drones during their 12-day war in June 2025, Israeli officials had claimed interception rates approaching 99 per cent for drones and 86 per cent for missiles.

Though most independent assessments broadly confirm the high effectiveness of the Israeli BMD yet, they also allude to those outcomes having been, at least, partly dependent on American support in early warning systems, prioritisation of defended assets, and controlled escalation dynamics.

According to one such assessment, in addition to Israel’s own Arrow missiles and other defences, the United States had directly engaged in neutralising many such threats, deploying over 150 Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) interceptors and approximately 80 Standard Missile-3s (SM-3).

Hence, engaging Israel alone may not suffice, and could entail expanding the partnership to Washington DC, which implies acquiring some of the American interception capabilities at some point in time.

Israel’s experience offers valuable lessons; that BMD is not such an easy option of a plug-and-play as it is often made out to be.

The US theatre systems: A Standard Missile-3 fires from a US destroyer (left), and a THAAD system fires from a road-mobile launcher

Also important to underline is the fact that compared to Israel, the scale and complexity of India’s geography and threat vectors happen to be radically intriguing, given that India’s two immediate adversaries — China and Pakistan — have expanding nuclear and missile stockpiles.

Defending a compact territory of 10 million citizens is fundamentally different from shielding a continental-sized country of 1.4 billion people. Scholars also often urge for reassessment of such exorbitant investments in static missile defence systems against dynamic threats that can surely reduce vulnerability but not eliminate it altogether. Also, any overconfidence in such defensive shields risks destabilising deterrence relationships.

Lasers and the changing cost curve of interceptors

Perhaps the most consequential — if still uncertain — element of Prime Minister Modi’s visit is Israel’s reported willingness to share high-energy laser defence technologies.

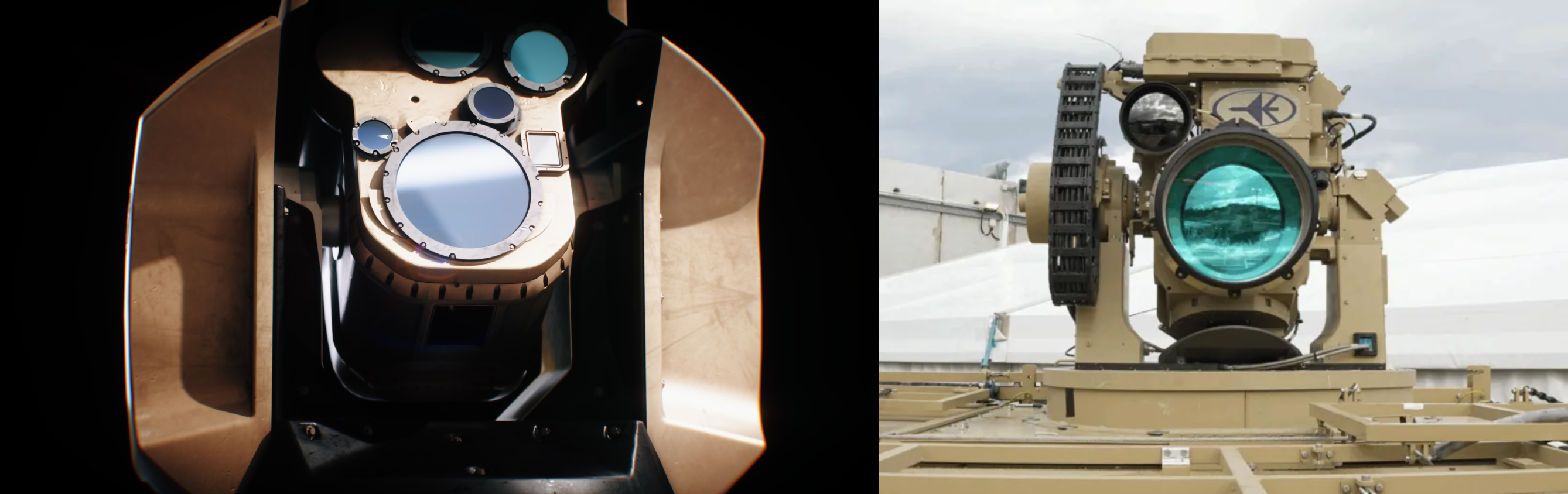

Israel is a pioneer and world leader in operationalising directed-energy systems, christened the Iron Beam, which promise to transform missile and drone defence by drastically lowering per-intercept costs and enabling rapid, repeated engagements.

Directed energy platforms of the Iron Beam system

For India, facing the prospect of drone swarms and rocket saturation along multiple fronts, such technologies are undeniably attractive.

But as of now, these laser systems remain only complementary rather than substitutive to Israel’s BMD systems. Their weather dependence, power requirements, and range limitations mean that they cannot replace kinetic interceptors.

Israeli analysts themselves emphasise that lasers are but a part of a mixed architecture rather than a standalone solution against missile and drone strikes. India’s challenge will be to integrate such systems without creating unrealistic expectations about their near-term effectiveness.

Equally critical is building cooperation on long-range stand-off weapons and loitering munitions. India’s operational experience during Operation Sindoor — where Israeli-origin systems such as Harpy loitering munitions were reportedly used to strike terror sites — has reinforced New Delhi’s belief in the efficacy of a penetrating surgical strike.

These systems also align well with India’s broader doctrinal shift toward disabling enemy sensors, shooters, and command nodes early in a conflict, rather than relying solely on attritional warfare. This also calls for calibrating these systems to India’s specific operational requirements, which provides scope for joint research and development, rather than outright acquisition, as strategically important.

From buyer–seller to joint development

A notable feature of the current phase of ‘Make-in-India’ driven India-Israel defence cooperation has been India’s emphasis on co-research and development, and co-production and exports. The groundwork for this new format was laid during Defence Secretary R K Singh’s visit to Israel in November 2025.

This was followed by last week’s Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) signed during a seminar held in New Delhi for Israel’s defence export directorate, SIBAT, and India’s Society of Indian Defence Manufacturers.

For long, India has been Israel’s biggest defence customer, accounting for over 34 per cent of its total exports during 2020-2024. Earlier last month, India’s Defence Acquisition Council cleared a proposal to procure Israel’s Lora and Rampage missiles, Spice-1000 precision guided bombs, radars and other defence equipment worth USD 8.7 billion.

However, this is being aligned with India’s long-standing aspiration to move beyond imports or licence production with supplier controls and monitoring. Also, Israel, unlike many suppliers, has shown a greater willingness to localise production and share select technologies.

Still, experts caution against overstating such openness and trust, given that India-Israel strategic partnership may become hostage to estranged India-US ties. Also, Israel’s most sensitive technologies remain closely guarded, and technology transfer often comes with operational, legal, and political constraints that Tel Aviv may not be able to set aside.

Saudi prince Mohammed Bin Salman (left), PM Narendra Modi (centre) and US President Joe Biden (right) at an IMEC meeting

The real test for Prime Minister Modi’s visit, therefore, will be to ensure a further push to their partnership, moving from procurements to joint development projects. This could help in developing and delivering scalable, affordable, and maintainable systems, without which bespoke platforms will continue to strain India’s budget and logistics.

Building such an organic partnership will have its own share of difficulties. But piecemeal careful calibration has become increasingly the hallmark of India’s increasingly confident West Asia diplomacy.

India’s inclusion in President Joe Biden’s I2U2 (India, Israel, UAE, United States) Quad of 2021 and the IMEC (India, Middle East Europe Economic Corridor) initiative of 2023 reflect global endorsement of India’s manoeuvrability in treading through its alignments in this turmoil-ridden Middle East.

India, for instance, has gradually de-hyphenated its relations with Israel from Palestine, trying to steer clear of bloc politics. But while India no longer allows its Israel policy to be vetoed by its Palestine policy yet, the second India-Arab League Ministerial meeting in New Delhi last month had seen India reiterating its policy of multi-alignment and its faith in a two-state solution for Palestine.

India also recently endorsed a United Nations statement criticising Israeli actions in the West Bank, though it was immediately followed by an official clarification distancing India from the document’s drafting.

New Delhi has also been recalcitrant about President Trump’s Board of Peace and attended its inaugural meeting last week only as an observer by sending its Chargé d'affaires from its Embassy in Washington DC.

The challenge for India also lies in managing perceptions — both in the Arab world and domestically — about its simultaneous pursuits of normative commitments, strategic realism and interest-based multi-alignment as well as issue-based partnerships.

Leader-level convergence, institutional limits

The personal chemistry between Prime Minister Modi and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has undoubtedly successfully accelerated their bilateral engagement across several sectors.

Prime Minister Netanyahu last week announced Prime Minister Modi’s visit during his address at the Israeli Defence Forces' young officers’ Graduation Ceremony. While talking of “tightening alliances with allies” and calling India a “gigantic power,” Netanyahu has also invited Prime Minister Modi to address the Israeli Knesset (parliament), which underscores the political warmth from both sides.

Yet, history suggests that leader-driven diplomacy must be institutionalised to ensure endurance to deliver in the long run. Changes in domestic politics — whether in Israel, India, or the United States — can alter their strategic priorities.

Sustaining cooperation, especially in sensitive domains such as missile defence and advanced technologies, will depend less on rhetoric than on deeper support from their bureaucratic coordination, funding commitments, and realistic and shared threat assessments and strategies.

Israeli officials often describe their partnership with India as one of agility meeting scale, implying the use of India’s 1.4 billion-strong nation to scale their breakthrough technologies. Israel offers innovation, rapid prototyping, and operational feedback.

India, for its part, offers production capacity and long-term demand. Artificial intelligence, sensor fusion, and data-driven command systems are emerging as critical enablers across defence, agriculture, and water management.

There is truth in all these complementarities, and yet there also remains some gap between India’s vision of restraint and readiness and Israeli focus on precision and preemption.

What this visit signals?

Prime Minister Modi’s visit to Israel this week, therefore, can be best understood not as a triumphant leap but as a measured bet to move piecemeal.

India is betting that a selective partnership with nations like France and Israel can advance its defensive capabilities without undermining strategic stability or diplomatic flexibility. Israel, in turn, has been facing stringent export controls with European nations and sees India as a long-term partner capable of absorbing and scaling its advanced technologies.

Whether the partnership with Israel makes India’s Mission Sudarshan Chakra a credible shield or remains a politically resonant aspiration will depend, of course, on execution, not announcements. What is clear, however, is that India is no longer content to rely solely on deterrence by punishment.

It is experimenting — cautiously — with deterrence by denial, which remains a necessary, if not sufficient, condition for reaching its Viksit Bharat finish-line. This shift in India’s doctrinal thinking alone makes Prime Minister Modi’s Israel visit strategically significant.

Not because it promises invulnerability, but because it reflects a more complex, technologically informed, and risk-aware Indian approach to national security. This is vital in an era of ever-intensifying missile competition across its periphery, and self-help being its only reliable strategy.

Follow us on WhatsApp

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X @vudmedia

Follow us on Substack