20 February 2026

In The Polity’s October 2024 ground report titled “Are India’s babus above the law: At least, the government has no data to prove otherwise,” we illustrated how the top echelons of the Indian bureaucracy seems to be enjoying some form of immunity and protection from the justice system, which has allowed them to function without much accountability and overbear on the citizenry. While this remains a legacy of the colonial era, the Indian bureaucracy continues to operate like an elitist and quasi-feudal monolith with a nexus of pelf and power which continues to overshadow the nation’s attempts at transition into a modern state, says Professor Shantanu Chakravarti, in this 5th edition of Glimpses from an Eastern Window.

Text page image: A view of North Block in New Delhi’s Raisina Hills, where the Home and Finance Ministries function

Banner image: President Draupadi Murmu with the 2020 batch of Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officers, photo source: President’s Secretariat

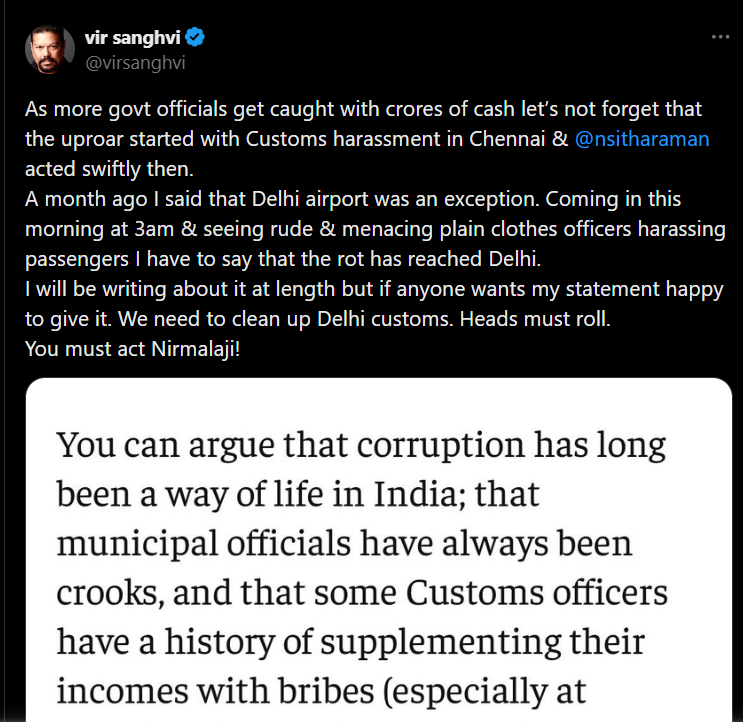

Veteran journalist Vir Sanghvi’s recent tweet concerning harassment and intimidation tactics by the customs officials against him and his wife while returning from a foreign trip at New Delhi airport has highlighted a problem which virtually all Indians face – stiffness of the officialdom and bureaucratic apathy, along with the embedded corruption prevailing in state-controlled institutions.

In the virtual world we now love to live in, Sanghvi’s comments and opinions, expressed through his numerous features and columns, generated reactions and counter-reactions, in favour or against.

In one such comment put up on LinkedIn, Ratun Lahiri, Senior Advisor at Unicorn India Ventures, writes:

“I do not know Vir Sanghvi and have no opinion of him. This is not an indictment of an individual. I write because the sense of entitlement in his written word astonishes me. I write because I am shocked by the egregious imbalance of power. The accuser, Vir Sanghvi, leveraged and even misappropriated every avenue open to him as a journalist to trash faceless, voiceless customs officers simply doing their job, who may have erred (or not) but have no means to respond. The accuser’s privilege ensured an online lynch mob was quickly assembled, guilt was assumed, and reputations of hapless customs officers were ruined who may have never left Indian shores but diligently guard India’s entry borders every day.”

While both sides may have their points, the truth, like in most cases, lies somewhere in between. Officialdom and bureaucratic blocks and apathy (along with unprofessionalism) continue to haunt ordinary Indians and have been aptly depicted through myriad cultural expressions.

One could think of R.K. Laxman’s ‘Common Man’ cartoon series, which brought out the difficulties faced by ordinary citizens while dealing with the government agencies on a daily basis. There is hardly anyone among the ordinary Indian citizens (popularly described as the ‘aam aadmi’) who has not faced any systemic hurdles or bureaucratic harassment in some form or other while dealing with public offices or public authorities.

Image: Cartoonist Shekhar Gurera's tribute to R.K. Laxman and his 'common man'

The famous Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gayne Bagha Bayne, a fantasy movie released in 1969, had the evil minister of the Halla kingdom (played by the veteran Bengali comedian Jahar Ray) advising his informer, “If you don’t know what people need and want, can you stop them from getting it?”

The Indian officialdom seems to have seriously adopted that line as their mantra or raison d'être and working principle. The bureaucracy and its notions of privilege, however, have come to be accepted as normal by people. It makes news only when there is a self-goal scored, an abuse of office revealed, or one amongst the privileged gets a taste of reality and expresses his or her disappointment and decides to tom-tom about it.

Usually, it makes instant news. For the rest of the underprivileged commoners, it is hardly regarded as anything new and is accepted as normal.

Historical roots of babudom

The bureaucratic stranglehold of India and its privileges, however, is not new. The progressive indigenisation of the Indian Civil Service (ICS) in the colonial times witnessed a spurt after the end of the First World War. They would continue to operate in independent India.

India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru’s speeches and writings during the 1940s and in the post-1947 period, continued to reflect a certain wariness about the ICS (and the new Indian Administrative Service), but the earlier trenchant criticism as reflected in his Autobiography had changed.

Image: Indian civil servants, circa 1890, photo by Bourne and Shepherd, sourced from National Portrait Gallery, London

According to historian David Potter, “Whether or not the ICS survived was probably less important to Nehru at that time than other aims like achieving political independence and becoming Prime Minister. Dropping the demand for ICS abolition in the 1940s made sense to a man who aspired to political leadership of the Indian state using a fairly conservative Congress as his base of political support.”

Analyst Amit Dasgupta feels that the inclusion and continuation of such men from the ICS provided a balance and long-term stability to the administrative structure in independent India. “With their professionalism,” writes Dasgupta, in his recent study of the three veteran ICS men in foreign service – Sir G. S. Bajpai, K. P. S. Menon and Subimal Dutt – “realism and pronounced political views, they partly assisted and partly formed a counterweight to an initially inexperienced, often overburdened prime minister, whose course more than once was guided by emotions and predispositions, and not always to the benefit of India.”

Such claims, even if accepted, could not hide the fact that their continuation imbued India’s projection of an antiquated policy not considering the available alternatives and changing dynamics of post Second World War global politics.

One major disappointment expressed in many circles was the perceived continuity in administration having facilitated a smooth transition and transfer of power as India became independent, but also retaining the dominant role of the old guards led by the erstwhile ICS.

Veteran journalist Binay Mukhopadhyay (using pen name Jajabar), in one of his belles lettres on his experiences in New Delhi covering the visit of the Cripps Mission in India, commented, “ICS is not a profession but a race. As the Holy Roman Empire was not holy, nor Roman or an Empire, likewise, the Indian Civil Service was not Indian, certainly not civil and did not have an iota of service in it.”

Noting his first impressions of the newly constructed city of New Delhi in his diary, Mukhopadhyay comments, “if Jamshedpur could be termed as a steel-town, then New Delhi is a city of ‘steel-frame.’ An entire city has grown around the Secretariat…Power and honour here is to be sourced through the pages in the India Gazette.”

Another bitter critic was Dr Hiranmoy Ghoshal (1908-1969), the veteran linguist and scholar who had served with the government of India in various capacities, including completing a stint at the Indian embassy, Moscow, as Additional Secretary (Cultural Relations) between 1947 and 1951.

The main failure, according to Ghoshal, was the continuance and enhancement of the status of the ICS, derisively mentioned as the ‘Service-wallahs’ by him. “The Congress leaders,” writes Ghoshal, “had not the foggiest notion of administration and offered the actual governance of the country on a platter to those Service-men they had slanged in their speeches and writings.”

As a result, Ghoshal writes in his diary, the country had to make a serious compromise and be “consigned back into the hands of a reactionary clique which had specially been trained in colonial administration, which did not see beyond its own model… Thus, all future progress of India, social, political and economic, was finally written off. The new “Slave dynasty” of India ruled the country on two principles: Cry havoc! And Cry halt!”

Embedded elitism in Indian society and its enduring legacy

While India became independent in 1947, the political independence made the socio-economic and cultural distinctions between the privileged and the hoi polloi starker in character.

Image: Seva Teerth-2, among the new buildings along Kartavya Path (Rajpath), which will house the Cabinet Secretariat, photo courtesy: Creative Commons

Historian Nayantara Pothen, in her book Glittering Decades, New Delhi in Love and War, vividly describes the nature of India’s transition in 1947:

“In order to secure their government, the new leaders of independent India further adapted and appropriated the symbols of authority and control used by the previous imperial masters, and which they themselves had also used in the past as political tools…Indeed, a little girl would describe the excitement of the Independence Day celebrations in 1947 as ‘Mr Nehru’s Coronation’ and the ayah of former ICS officer, B. B. Paymaster, would watch the first Republic Day parade in 1950, see the President drive past in his horse-drawn carriage and ask Paymaster if this was their new King. The symbols of British authority retained their potency and were used by the new Indian political masters.”

Pothen further argues in this book that it is “after 1952 that the old indigenous Western-educated elite groups would begin to lose their primacy in government as a new, younger generation of politicians and intellectuals of diverse backgrounds with their own ideals and interests, began to infiltrate the once privileged circle…Nehru’s comment that he would be the last Englishman to rule India can be regarded as a statement for an entire generation of Western-educated Indians.”

Elitism, however, did not die out with the disappearance of the old order. In a country transitioning from pre-modern to modern, latching on to symbolic representations of power and elitist symbols proved to be intoxicating and essential for members of the new order, who were taking over.

This was not restricted to bureaucracy alone, but was certainly helped by the state psyche, which had been shaped and influenced through their notions and interpretation of privileges. The contagion spread across and vertically from top to down.

Image: The crest of the Indian Administrative Service (left), and a plaque to commemorating the Civil Service of British India (right)

Politicians, bureaucrats, academics and professionals, irrespective of class or caste differences, regional divergences, even today, eagerly compete with each other to acquire, extend and restrict power and privileges amongst themselves, family members and friends.

Attempts to transform the landscape of Lutyens Delhi or projecting India as a civilisational state through multiple official channels could be regarded as only as minor attempts, which cannot and will not seriously challenge the problem.

India, in a sense, continues to display signs of being a ‘quasi feudal’ state where elitist domination is not based on traditionalism but a nexus of pelf and power which continues to throw an ominous shadow over the nation’s attempts of transition into a modern state.

Follow us on WhatsApp

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X @vudmedia

Follow us on Substack