03 March 2026

Asia Watch by Professor Swaran Singh - IV

The relationship between the European Union (EU) and China, the world’s two prominent economic powerhouses, has been rocky, echoing the tumultuous times which is also shaped by US President Donald Trump’s volatile actions and polices. Hence, there is little hope of breakthroughs at the EU-China summit in Beijing in the coming week, which will also mark the golden jubilee year of their diplomatic ties. At the core of the troubled relations are numerous divergences and disputes, including access to rare earths, protectionism, the Ukraine war and human rights, among others, which make convergence and dealmaking an uphill task, says Professor Swaran Singh, in this fourth edition of the Asia Watch.

In the coming week, Beijing will host the landmark China-European Union (EU) summit to mark the golden jubilee of their diplomatic relations. However, any hope of Trump’s tariffs pushing these two largest trading powers into crafting some innovative alternatives to the American economic leadership stands crippled by their persistent disjunctions and insinuations that betray mutual misgivings.

To begin with, Beijing and Brussels usually alternate as summit hosts. But, earlier this year, President Xi had snubbed the EU leadership by refusing to travel to Europe. This time around, in Beijing as well, President Xi may meet the visiting delegation. However, the discussions will be chaired by Premier Li Qiang, who is now recognised as the second in line.

Furthermore, this summit, which was originally planned for two days, has been curtailed to a single day (July 24) with the EU delegation slated to head home the very next day.

Image: Christopher Soames's meeting Premier Zhou Enlai in May 1975. Photo courtesy: Brussels Institute of Geopolitics

Image: Christopher Soames's meeting Premier Zhou Enlai in May 1975. Photo courtesy: Brussels Institute of Geopolitics

Answers to this simmering disquiet in China-EU interactions are being explored in mushrooming speculations about Xi’s leadership at home, as also in unsustainable, yet increasing, dependence of the EU on China. No earth-shaking outcomes, therefore, are expected from this otherwise high-profile summit that should see them issuing a modest press release rather than any comprehensive joint communique with timeline-driven initiatives.

The European indulgences

It was on 4 May 1975 that Sir Christopher Soames, the son-in-law of Winston Churchill and then Vice President and Commissioner for External Relations of the European Economic Community, flew to Beijing and hosted a lunch for Premier Zhou Enlai, proposing the start of diplomatic relations.

This was a puzzle of sorts, then. China, largely a pariah, had a GDP of mere USD 163 billion compared to the EEC’s combined GDP of USD 1.69 trillion that was growing rapidly under the G7 global leadership.

Their incompatibilities were not limited to their economic size alone.

By all means, this was a risky indulgence given that the Cultural Revolution-ridden China was fast sliding into its long and tumultuous transition from Chairman Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. As a result, nothing much happened between Europe and China for the next 12 years.

It was in 1985 that the Trade and Cooperation Agreement was signed between the two, followed by institutionalised diplomacy initiated through the China-EU summit in 1988.

By this time, Deng had firmed up his grip on power and unleashed economic opening up and reforms to set in motion China’s unprecedented rise. This was to see their bilateral trade grow from USD 2.4 billion in 1975 to USD 23.51 billion in 1988, to USD 68 billion in 2000 and USD 785 billion by 2024.

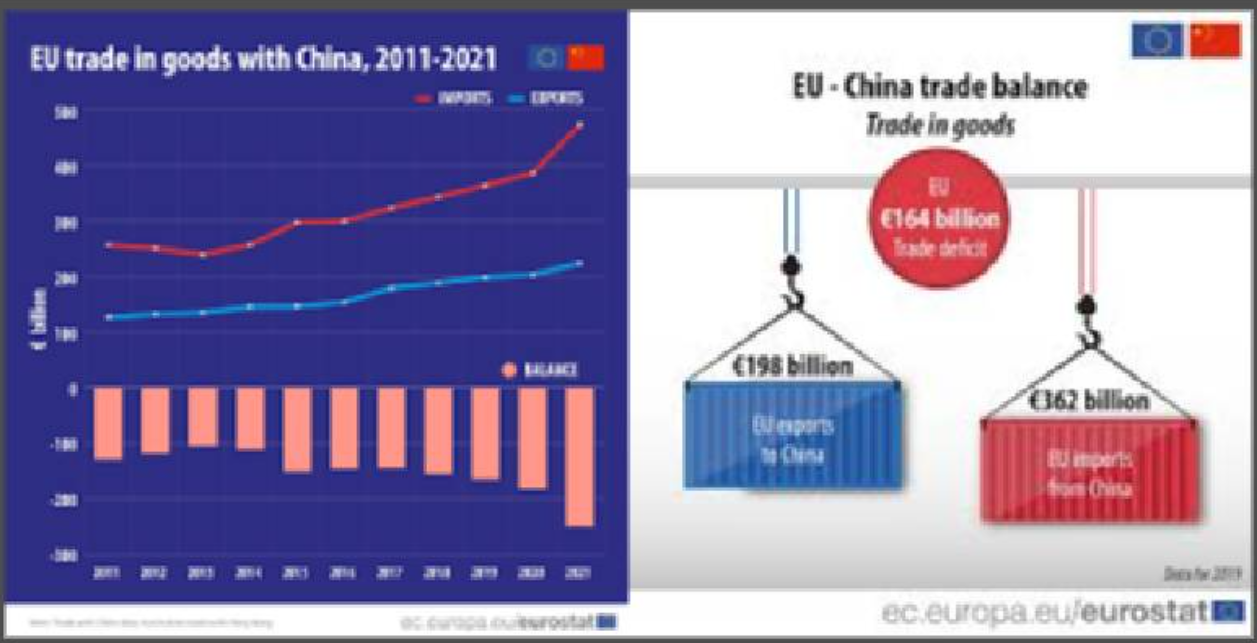

However, two things make this inordinate rise in their trade disconcerting: the growth rate has now become sluggish at 0.4 percent, and trade has largely become one-sided with a formidable USD 300 billion plus deficit in favour of Beijing.

China has used this trade surplus by investing extensively in Europe and cultivating EU members. In 2024, China included construction contracts worth USD 71 billion, along with around USD 50 billion pledged in other sectors.

The result: today, 29 European states, including 17 of the 27 EU members, have joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and 20 of 27 are members of China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Then there are investments by China that are not counted as part of BRI.

Tech rivalry and energy transition

However, more than China’s economic prowess, the EU today faces China’s techno-nationalism-driven interference in global governance structures and processes. China’s formidable ‘system shaping’ power today flows from its USD 20 trillion economy and its expanding leadership in technology.

Meanwhile, China also continues to have a lion’s share of over 32 percent in global manufacturing, which makes it the world’s largest trading nation since the turn of this century. The resultant outcome was China emerging as the largest trading partner with most countries.

China’s technological strides in domains like 5G, Artificial Intelligence (AI), semiconductors, and so on, have triggered alarm across the Western world. At the same time, many of these nations remain dependent on China’s supply chains, especially in fulfilling their energy transition commitments, where again China has a clear lead.

Along with China’s rare earths, these technologies form a critical part of the EU’s shift to clean-energy infrastructure, including solar panels, batteries, EV motors, and turbines. This makes the EU vulnerable to Beijing.

Image: The world's largest rare-earth mine, Bayan Obo deposit, in Baotou City, China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Photo courtesy: CGTN

Image: The world's largest rare-earth mine, Bayan Obo deposit, in Baotou City, China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Photo courtesy: CGTN

The European Union needs China’s state-backed scale to hit its net-zero goals, even if doing so undercuts its domestic industry and triggers security concerns. Especially on semiconductors and software, Brussels has been ramping up its ‘de-risking’ strategies by exploring subsidies, alternative supply chains, and new trade regulations.

While China wants Europe to steer clear from the US tirades against Beijing, the EU continues to align with those American calls for tighter tech controls, thus identifying China amongst their competitors, if not adversaries.

China’s rare-earth dominance

Today, the reality is that the industrialised world seems collectively aggrieved by China’s dominance in the processing of rare earth materials. According to the European Commission, the EU relies on China for 98 percent of its rare earths supplies as well as rare earth magnets.

At this summit, therefore, the EU leaders will hope to dissuade China from weaponising this near-complete control over rare earth elements (REE) that remain critical for building wind turbines, electric cars, defence systems, and other electronics.

China, on the other hand, cites American pressures to explain the tightening of its export licensing policies. No doubt, China has since offered exceptions of ‘green channels’ for quicker licensing of rare earth exports to the EU, yet its uptake allegedly remains slow. Without concrete commitments on licensing approvals, tariff rollbacks, or agreed price floors replacing EV tariffs, both sides will continue to feel aggrieved.

This has seen both China and the EU approach the World Trade Organisation redressal mechanisms, thus adding to their extant fault lines.

At the top of their priorities, as EU leaders arrive in Beijing this Thursday, they may hope to secure unrestricted or long-term access to China’s REE using its ‘green channels.’ However, the experience so far has been one of stalled licenses and customs hold-ups. This raises concerns of China using its REE as a geopolitical tool to pressurise Brussels into softening its stance on EV tariffs or other trade probes on China.

Needless to emphasise, the half-century of deep, laboured economic cooperation may present itself as a significant feat. Yet, when Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, and Antonio Costa, President of the European Council, arrive in Beijing the coming week, they must go beyond optics and address their core disputes on trade imbalances, market access, subsidies, values and the fast-transforming Indo-Pacific geopolitics.

Trade deficit to market access

First and foremost, the formidable and persistent trade deficit drives the EU’s worst anxieties.

China’s suspected state subsidies feeding its exports, especially in electric vehicles (EVs), industrial machinery, and renewables, have seen the EU slapping additional tariffs on Chinese EVs. China, in turn, has retaliated with anti-dumping duties on the EU brandy and initiated probes into EU pork and dairy.

China has also restricted procurement access in sensitive sectors like medical devices.

Market access remains the other related core EU concern, where it demands reciprocity from Beijing. Despite being China’s largest trading partner, European companies complain of systemic hurdles to entering or operating inside China. They see China’s laws on cybersecurity, procurement, data storage, and foreign investment tilted in favour of domestic state-owned enterprises.

This has seen the EU invoke its emergency “Anti Coercion Instrument” to penalise economic coercion, such as recent export curbs on rare earths and industrial tariffs.

Last month, the EU Trade Commissioner Marcos Sefcovic told China’s Commerce Minister, Wang Wentao, who was visiting Brussels, that China’s “impressive rise must not come at the expense of the European economy.” Yet, distinct from Trump’s ‘reciprocal tariffs,’ Sefcovic asked for ‘reciprocal access’ to markets sweeping aside barriers in agriculture, cosmetics, infant formula, and government procurement in China.

This meeting, however, was followed by the EU refusing to convene the usual High-Level Economic and Trade Dialogue, underscoring the gap between China’s actions and promises.

The Ukraine war and human rights

The Ukraine war has added another bone of contention between China and the EU.

Kaja Kallas, the former Prime Minister of Estonia who is currently the EU High Representative on Foreign Affairs and is a known critic of Russian President Vladimir Putin, had told Wang Yi during their 13th Strategic Dialogue in Brussels earlier this month “to immediately cease all material support that sustains Russia’s military industrial complex” and “to back a full and unconditional ceasefire” in Ukraine.

The EU remains aggrieved by China’s exports of drone parts and dual-use components fuelling Moscow’s war machine. China, for its part, denies supplying any military aid to Russia, even when EU officials continue to cite evidence of Chinese firms shipping missiles, avionics parts, and sensor tech using complex supply chains.

At this summit, therefore, EU leaders are likely to, once again, reiterate these concerns. They will urge Beijing to refrain from its dual-use exports to Russia and use its global influence to ensure an early end to this war. This implies asking Beijing to align closer to Western narratives.

Image: The author with Kaja Kallas, former PM of Estonia and currently the EU High Representative on Foreign Affairs, at Tallinn, February 2024

Image: The author with Kaja Kallas, former PM of Estonia and currently the EU High Representative on Foreign Affairs, at Tallinn, February 2024

China, in turn, might insist on the principle of neutrality and accuse the EU of unilateral pressure.

In addition to these economic and strategic issues, norms and values remain powerful determinants in China-EU equations. For example, the European Parliament continues to demand concrete milestones on human rights, like the release of political prisoners.

The EU remains sharply critical of China’s handling of human rights, especially in Hong Kong and Xinjiang. But the EU’s 2021 sanctions on Chinese officials over Uyghur repression had produced Chinese retaliatory blacklisting of four entities and ten EU lawmakers, including Reinhard Buetikofer.

Following the 2024 elections of the European Parliament, and ahead of this summit next week, China had lifted this ban on EU parliamentary exchanges, signalling a modest thaw but not a complete reset in their relationship. However, the European Commission has refused to reopen its shelved Comprehensive Agreement on Investment until China’s shows improvement in the European Union's human rights indices.

But in the face of several other critical issues in contention, human rights concerns may be mentioned at the summit but are likely to be camouflaged in generic verbal references to norms and may not appear in any formal communique.

Expected outcomes

With trade talks stalled, the REE licenses slow, and human rights in gridlock, expectations from the summit are bound to be restrained.

At best, we may expect a modest press release, token gestures and adjustments on EV prices, but no commitments from China is likely on its dual-use exports to Russia. There would be open-ended discussions on the climate crisis and nuclear nonproliferation to create symbolism for China while the EU sticks to principles.

On the flip side, the EU has to begin exploring alternatives for REEs or live with tardy delays in China’s exports. On the other hand, while the EU’s cooperation with China will invite US ire, its US-driven caution is likely to trigger China’s anxieties.

Image: Ore-laden vessels leave a Chinese port. Photo courtesy: Xi's Moments

Image: Ore-laden vessels leave a Chinese port. Photo courtesy: Xi's Moments

At home, EU leaders face domestic backlash from Chinese exports, leading to job cuts in sectors like automobiles, batteries, and other tech industries. The Far Right Eurosceptics could exploit any deal as capitulation. The via media of a limited compromise will preserve the EU’s trifurcated China label as a cooperative partner, systemic competitor, and strategic rival.

Thus, the China–EU Summit in their 50th year of diplomatic relations will be a milestone of reflection. It will showcase their cautious bridging through technocratic continuity and diplomatic courtesy, while it is not expected to resolve their persistent irritants of trade asymmetries, industrial policy differences, human rights, supply-chain concerns, and geopolitical anxieties.

Both sides could return from the summit touting progress and seeking value in optics rather than untying knots, especially those around China’s chokehold on its rich strategic minerals’ repository.