16 December 2025

The intensity of conflict between Thailand and Cambodia in recent months – emerging from unresolved historical disputes and a contested border with cultural fault lines – has baffled international observers. What was initially seen as minor border skirmishes has, in recent months, escalated into persistent military stand-offs, causing a recurring humanitarian crisis. With the intervention of the Nobel-seeking US President Donald Trump leading to multiple accords and ceasefires between the East Asian neighbours, which, though failed to endure even for a few weeks, parallels are now being drawn with similar endeavours in Gaza and Ukraine. At the heart of the recurring conflict is the fragility of imposed accords and piecemeal truce plans that are driven by political expediency rather than concrete measures of peacebuilding, says Professor Swaran Singh in this 13th edition of Asia Watch.

Text page image: US President Trump and Prime Minister of Malaysia, Anwar Ibrahim, with Anutin Charnvirakul and Hun Mane, the premiers of Thailand and Cambodia, respectively, at the signing of the 26 October 2025 peace accord in Kuala Lumpur, photo source - White House

Home page image: A map depicting the disputed territory in the Thailand-Cambodia conflict, photo source - Conflits

Banner: The Prasat Ta Muen Thom, one of the Khmer-Hindu temples, which is at the heart of the border dispute, photo source - Wikipedia Commons

When explosions once again shook the frontiers separating Thailand and Cambodia during the wee hours this Monday (December 8th), it was clear that a tenuous peace that hung over this volatile East Asian border has once again failed to endure. The resumption of hostilities also meant that the six-week-old, latest version of the ceasefire agreements between Thailand and Cambodia had also collapsed.

These two member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) had agreed to a ceasefire first on 28th July, and then on 7th August and finally on 26th of October, the last one notably in the presence of President Donald Trump and Prime Minister of Malaysia, Anwar Ibrahim.

While the US Department of State has, on Tuesday, urged “the immediate cessation of hostilities, the protection of civilians, and for both sides to return to the de-escalatory measures outlined in the October 26 Kuala Lumpur Peace Accords,” it is now evident that the conflicting parties have also now made the breach of peace their new normal.

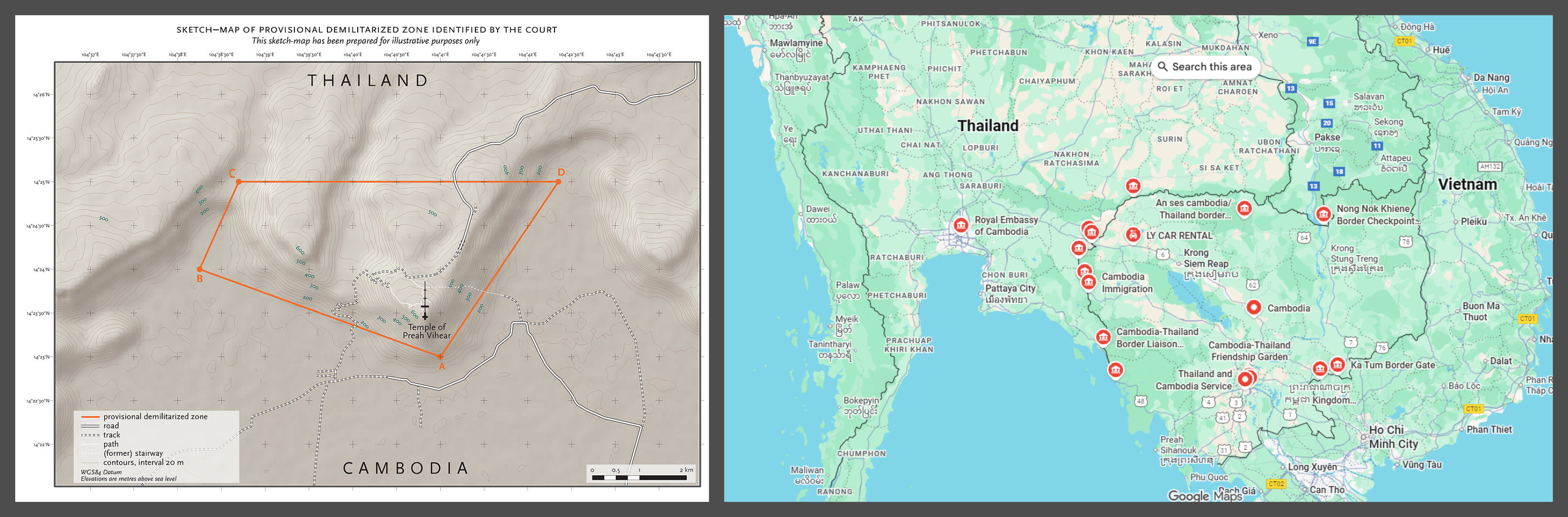

Image: A map of the demilitarised zone as per the International Court of Justice (ICJ) verdict (left), and the larger map view of the Thai-Cambodian border (right)

It is equally important to underline that, besides the last one, which was signed at the 47th ASEAN summit in Kuala Lumpur, all these agreements had involved ‘duly-recognised’ interventions of President Trump.

No doubt, these ceasefires had their limitations; yet few had expected the last one to unravel this fast. Nothing embodies this better than the pace with which the first wave of air strikes has happened and fighting spread across their borders, causing casualties in multiple locations, and border districts along the Cambodia-Thailand border have to be evacuated.

It took only hours for the region to edge back again into a major conflict, the roots of which continue to defy solutions and can be traced back to more than a century, if not more.

Prima facie, this Southeast Asian crisis is not just a story of two sides trading fire. It is a case study in how ceasefires fail when political expediency short-circuits piecemeal negotiations. From this perspective, the latest Thai-Cambodian face-off also has lessons for President Trump’s other peace plans for Gaza and Ukraine.

When deep-rooted historical narratives along deeper binaries remain unaddressed, and when regional institutions lack the requisite leverage to enforce peace, inter-state conflicts keep flaring again and again.

This conflict, thus, presents an apt example of peace initiatives that become unsustainable and have implications not just for the conflicting parties but for the larger region as well.

Negotiated under pressure, accepted with hesitation

The Thai-Cambodian truce in question was first signed in late July 2025, following five days of clashes around their centuries-old disputed borders. According to reports, at least 38 soldiers from both sides were killed, and more than 300,000 civilians fled the border districts on both sides to their respective interiors during that brief but destructive flare-up.

ASEAN was quick to step in to broker the ceasefire; the current ASEAN Chair, Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim personally steering the emergency talks, and external pressure from the United States and China was pushing both sides to agree to an accord as fast as possible.

Speed, it seems, was privileged over substance, and the ceasefire halted fire but resolved nothing much. No demilitarised zone was created and no neutral monitors were deployed. Heavy weapons stayed in place, and minefields were neither mapped nor jointly inspected and secured. Most critically, no roadmap was agreed to take these talks forward and initiate efforts for border demarcation.

Hence, the bone of contention for their repeated border clashes remained unaddressed. This ceasefire agreement, no doubt, bought time but not trust. And time, without trust, has once again allowed the old disputes to resurface.

Hurriedly hammered superficial peace plans fail to look beyond the firefighting and miss deeper structural fault lines. Although modern high-resolution maps for the 820-kilometre Thailand–Cambodia border exist, yet, a significant portion of the line has never been mutually agreed and/or demarcated on the ground.

Image: The Temple of Preah Vihear, which is among the Khmer-Hindu temples at the heart of the border dispute, photo source - UNESCO

That ambiguity has created a situation where, repeatedly, every patrol, every observation post, and every road repair runs the risk of being interpreted as an intrusion that can trigger tempers.

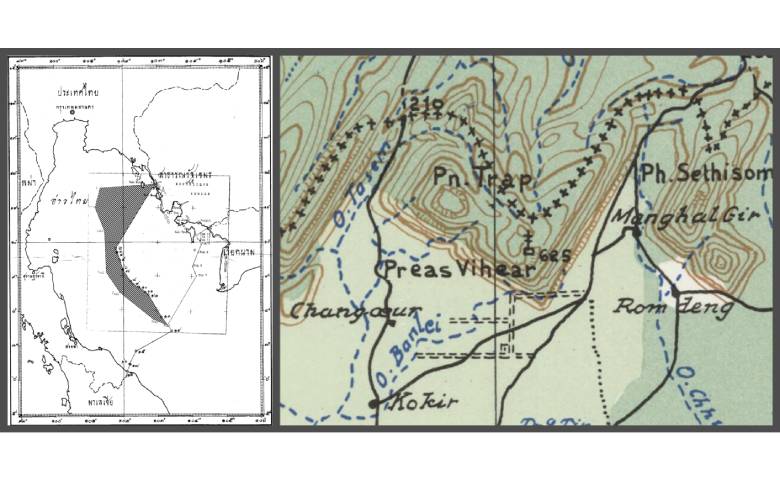

The Thai claims go back to 1954 when they finally took control of these frontiers based on the Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1904, one of the several treaties signed to resolve the 1893 crisis between the Siamese Kingdom and the French Colony in Indochina, encompassing present-day Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

But, for Cambodia, some of these territories are part of the identity of its Kingdom. Most sensitive amongst these is the region around its 900-year-old Preah Vihear temples. In 1962, the International Court of Justice had ruled that the ancient temple belonged to Cambodia, a judgment that was reaffirmed in 2013.

The surrounding areas of this temple, however, remain contested. Over the decades, the nearby hills, escarpments, and forested slopes have become militarised. When troops operate so close to each other, even one misstep can escalate into a skirmish. But these tensions are not limited to the military. They are tied to their national identity, historical narrative, and domestic politics.

In Thailand, the idea of losing land to any neighbour is politically explosive. In Cambodia, historic sites carry immense cultural weight and pride.

Political leaders on both sides face nationalist constituencies who demand firmness, not compromise. Such an environment makes even carefully negotiated agreements hard to implement. And, a hurried one stands little chance!

Landmine incidents broke the ceasefire

By early November, their October 26th Joint Declaration was already in trouble. On November 10th, four Thai soldiers were wounded in mine-related incidents. In such a charged environment, every wound is evidence of betrayal.

Accusing Cambodia of planting new landmines, Thailand suspended implementation of their peace agreement and halted the planned release of 18 Cambodian soldiers.

Phnom Penh, for its part, countered that the mines were remnants of older conflicts and were within Cambodian territory, and accused Thailand of encroachment while denying any proof of deliberate provocation.

Their hurriedly hammered ceasefire did not sufficiently address landmines. For instance, knowing that border areas were infested with landmines, the ceasefire agreement did not survey or secure these fields, leaving both soldiers and civilians at risk. Was it to be surveyed, it would have been possible to identify if Cambodia had laid new mines.

There were no neutral observers to verify anything, nor any third-party oversight; trust then was bound to be fragile. Such incidents exposed the fundamental weakness of the ceasefire, and each side was bound to turn such incidents into a political weapon.

Image: Overlapping continental shelf claims of Thailand and Cambodia (left), photo source - Wikipedia Commons, and position of the Temple and the border, which formed the basis of the ICJ judgement, photo source - H. Barrere

Thailand responded by suspending several aspects of the ceasefire. Cambodia protested these actions. The border communities, meanwhile, grew anxious. The truce was still technically in place, but operationally dead.

Early in December, Thai defence officials accused Cambodian units of repositioning troops and reinforcing contested areas with heavier weapons. While Cambodia denied these claims, in border conflicts, perception matters as much as reality. Once Thailand concluded that the repositioning indicated preparation for renewed fighting, it reacted with air strikes.

When fighting resumed, it signalled a sharp escalation, potentially threatening a regional crisis. As a major step upward from previous artillery exchanges, Thailand delivered air strikes, igniting panic among civilians, with border communities quickly evacuating.

Cambodian villages have been reportedly emptied out as families fled deeper inland. Thai residents along the frontier have also been moved from the most exposed districts. Within hours, the ceasefire was functionally over. Within days, it will become clear that it had never truly been alive.

Why ceasefires were always fragile

Let us enumerate some of the prominent omissions that have made successive Thailand-Cambodia ceasefire efforts unsustainable. These could also shed light on why the crisis could trigger regional instability and undermine the efficacy of ASEAN as the region’s prominent grouping, and may even have lessons for Gaza and Ukraine.

Image: People displaced by the conflict in relief camps, photo source - Childrenofmekong

1. It avoided the core issue - defining the border:

These repeated ceasefires have been without clarity about the land it is meant to protect and, therefore, too fragile to survive jingoistic misinterpretations. Parts of the Thailand-Cambodia boundary are undemarcated and leave military commanders on both sides to rely on contested colonial-era charts as modern national maps remain disconnected.

2. Ceasefires negotiated too fast for issues this deep:

The July, August and October truces were written under domestic and external pressures to stop bloodshed immediately. In effect, they amount to applying a political bandage on a geopolitical fracture. Genuine peace requires addressing deeper issues of national sovereignty, historical grievances, demilitarisation — issues too large to be negotiated in a few days’ time.

3. These lacked enforcement mechanisms:

Durable ceasefires rely on neutral monitors, verification teams and communication channels. Regional institutional roles can help create synergies. These ceasefires have had none of these inputs and variables. The absence of oversight means that each side monitors the other through its own intelligence, amplifying bias and suspicions.

Image: A Thailand-Cambodia border liaison point at Victory Bridge Crossing (left), and an immigration point on the border (right)

4. Domestic politics left no space for compromise:

Nationalist pressure on both sides makes any concession politically vulnerable. In such an environment, ceasefires are often treated as temporary pauses used to regroup rather than emerge as irreversible steps toward peace. Instead, such pauses must be seen as opportunities to build atmospherics for addressing complex, contentious binaries.

5. The borders remain heavily militarised:

Thousands of troops operate in close proximity, sometimes deployed only hundreds of meters apart. Landmines are implanted in the forested areas. Even when both sides intend peace, accidents like landmine injuries are unavoidable. And, in tense environments, accidents look like provocations.

What are the likely future trajectories?

1. Escalation into a larger conflict

This is what risk analysts take most seriously. The use of air power indicates a clear willingness to escalate beyond patrol skirmishes. If both sides continue reinforcing frontline positions or responding aggressively to movements across the disputed line, open conflict could persist.

Civilian displacement would likely surge, which would require humanitarian corridors. Furthermore, cross-border trade is destined to be impacted.

Image: The Cambodia-Thailand friendship garden in Phnom Penh

2. A return to diplomacy under deeper mistrust

Both governments may eventually realise that the cost of fighting is too high. But any new ceasefire must be seen as building on the last one. They, for instance, must institutionalise neutral monitoring teams, map and fence demilitarised areas, ensure functioning formal communication channels between local commanders and explore timelines for de-mining. Even with these, trust will take years to rebuild.

3. Long-term peace process with ASEAN at the centre:

The only durable solution is a scientific and politically binding demarcation of the border, supported by joint mapping, satellite surveys, and historical documents. A long-term treaty would need to be guaranteed by ASEAN or perhaps supported by its major international partners.

The question is whether there is political will on both sides to sustain such painstaking diplomacy.

The ASEAN, which is expected to take the lead, has been struggling to deliver even in the case of Myanmar. This is because ASEAN has historically kept aloof from bilateral conflicts and played a rather limited and largely symbolic role in internal or bilateral disputes.

Image: People queuing up at one of the border crossing points (left) and a truck crossing (right) along the Thailand-Cambodia border

Nevertheless, it did mediate in these talks in 2011 and now in 2025. But, amidst military clashes of this nature recurring in the Thai-Cambodian conflict, ASEAN clearly lacks any peacekeeping forces or monitoring teams and has no arbitration mechanisms or enforcement authority.

The influence of ASEAN depends only on persuasion, not pressure. When tensions rise quickly, persuasion is rarely effective.

A border at the crossroads

Repeated breakdowns of the ceasefires — especially the last one of October 26th — between Thailand and Cambodia were anticipated but perhaps not so rapidly. This is the predictable outcome of a truce built to stop gunfire, but not comprehensive enough to solve the historical baggage behind it.

The accords could have perhaps survived longer to create an atmospherics for addressing more contentious issues, which surely needs time.

For decades, these two countries have lived with a frontier that is both symbolic and strategic; both sacred and heavily armed. The crisis now confronting them is not simply a military clash but the entangled issue of national identity, which is built around their respective narratives of an unfinished historical agenda.

Unless they confront these real sources of tension — land, identity and political symbolism — any future efforts for peace will remain fragile and vulnerable.

Image: A Thai soldier confronts a snake during a joint-exercise with the Indian Army, photo source - PIB

As regards ASEAN, it remains the only regional body that both these parties to the conflict trust to a limited extent. But even with such novel tools — such as lightly-staffed ASEAN observer missions — the conflicting parties risk repeating the same cycle of emergency diplomacy followed by another rapid collapse into crisis.

In such a scenario, whether the regional stakeholders gear up for a deeper war or a renewed effort at negotiations will depend fundamentally on what both these kingdoms plan to do by themselves.

The world has seen what an externally-driven and rushed ceasefire has produced.

The pertinent question is whether these two can now take the lead to negotiate a sustainable ceasefire for themselves, where external players must play only a minimalist and complementary role to support initiatives of these two parties to the conflict.

Follow us on WhatsApp

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X @vudmedia

Follow us on Substack